Why Edward II paid a visit to Ightenhill

Earl Henry had to make provisions for the future of his estate and this was achieved when Alice married Thomas Plantagenet (otherwise Thomas of Lancaster), a minor member of the royal family. Thomas was the son of Edmund Crouchback, the younger son of Henry III and bother of Edward I. He was, therefore, cousin to Edward II.

Crouchback was the earl of Chester and first earl of Lancaster. He had been a major figure in the reign of Edward I and had known Henry de Lacy who had succeeded him as Viceroy of Aquitaine in 1296 when Edmund died. It was the children of these two men who now married.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThomas succeeded to the earldoms of Lancaster, Leicester and Derby, from his father, and effectively became earl of Lincoln and Salisbury through his marriage to Alice de Lacy. He also succeeded to the other de Lacy titles which included Lord of the Manor of Ightenhill but we know little of his local activities.

At a national level, Thomas was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, of the barons. His father, as had Henry de Lacy, had been fortunate in that the king, Edward I, whom he served was worthy of the title. Unfortunately, the new king, Edward II, was not. We have seen that when Edward II became king in 1307 he failed to attend his dying father rushing to secure the throne for himself.

The new king did this in company with his “good brother Piers” whom he quickly created Earl of Cornwall. Piers Gaveston had been banished from England by Edward I and was to suffer two further banishments at the beginning of the reign of his son, though neither were on the order of the king. The second of these had stated that if Gaveston returned, without the permission of Parliament, he was to suffer the ignominy of outlawry.

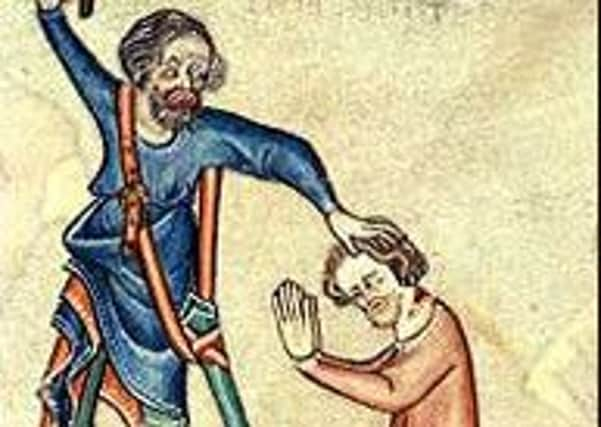

It is possible the king recalled Gaveston, in 1312, and they certainly met in the North-east but, when the barons found out, both had to flee. Alternatively, Gaveston returned to see his newly-born daughter. Whichever is the case, the barons eventually captured him, sent him for trial by his peers, one of whom was Earl Thomas, and, in bizarre circumstances, Gaveston was run through with a sword and beheaded.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe man responsible for the death of Gaveston was the earl of Warwick, the “Black Dog” as Gaveston had nicknamed him, but Edward did not forget the role played by Thomas of Lancaster in the murder of his friend.

What happened to Gaveston was because he had been Edward II’s favourite, though others suggested the king and Gaveston had enjoyed more than manly friendship. It was, however, through Gaveston that royal power was exercised in the early part of the reign.

The barons, led by Earl Thomas, were particularly put out when, a year after coming to the throne in 1308, Edward appointed Gaveston “guardian of the kingdom” when he himself set out for France to marry Isabelle, the daughter of Philip IV. When the king returned the barons demanded the dismissal of Gaveston. Edward consented but made Gaveston Lord Deputy in Ireland.

This made clear what the policy of the Crown was going to be. Earl Thomas and his baronial supporters came to the conclusion they were going to be ignored by the king and his favourites who would rule the country on his behalf. In 1310 Parliament appointed the Lords Ordainers to regulate the king’s household and reform his government.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey made recommendations related to the use of royal power. These would limit the king’s power to declare war without the consent of Parliament; ensure the great offices of state should be filled by Parliament, not the king acting alone and they advised that Parliament should be held at least once a year, not at the request of the king. There were other provisions, like the removal of taxes on wool and cloth, and a rule that no gifts could be made by the king without the agreement of the Ordainers.

After the death of Gaveston, there was an uncomfortable two years but, in 1314, the Scottish Wars resumed. Robert the Bruce had been active and many castles, formerly in the hands of the English, had been taken. Stirling still held out and Edward said he would lead a large army to Scotland, not only to relieve Stirling but to put an end to Robert’s activities. Unfortunately, this expedition ended in disaster at Bannockburn, in 1314, where Edward was heavily defeated.

The king’s policies had resulted in abject failure so he submitted to his great enemy, Thomas, who effectively became the ruler of England in the years 1314-18. However, Thomas could not prevent the incursions of the Scots into northern England and, in the latter year, his administration fell. At about the same time the Scots regained their independence from England once more.

Edward II took the opportunity to take more power to himself and, along with Hugh Despenser, and his son, he attempted to rule the country as he had with Gaveston a decade before. The barons were disgusted at Edward’s misrule and, under the leadership of Earl Thomas, they rebelled. Matters came to a head at the battle of Boroughbridge in 1322 when Thomas was defeated.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis time Thomas was at the mercy of the king but the latter was in no mood to forgive and forget. The earl was put on trial, found guilty of being a traitor and was sentenced to death. The only concession Thomas got from Edward was that, rather than being hung, drawn and quartered, as the law directed, Edward ordered beheading was enough. Perhaps the king had what happened to Gaveston in his mind when making his decision? The ignominy of Gaveston’s death was shared by Thomas in that he was executed in front of his own castle at Pontefract.

Before we finish with Earl Thomas, a man who should be more widely known than he is, it ought to be stated his influence did not end with his death. Last week I indicated there might be something of a surprise. Let me introduce it now.

Soon after Earl Thomas’s death, there were reports miracles had taken place at his tomb which had been constructed in a specially-built chapel at Pontefract. In the reign of Edward III, there was a petition to the king that he should ask the Pope for the canonisation of Earl Thomas and there was a popular veneration of Earl Thomas right through to the Reformation in the 16th Century.

The Earl was regarded as not only a champion of the Church, something of a second Becket, but also a champion of the people against the excessive use of royal power. In truth, he was an over-mighty subject who may have had some of the sympathies attributed to him. However, if the result at Boroughbridge been different, Thomas might have removed, from the throne, a weak and unpopular monarch sooner than this was actually achieved. Whether the Earl would have been a William Marshall, who preserved the royal succession on the death of King John in 1216, or a Henry of Bolingbrook, a descendant of Thomas, who took the throne for himself in 1399, we will never know.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are a few final things to say. The first is that the de Lacy estates, for some years in the 1320s, were in the hands of the king. On the death of Edward II, they were returned to Earl Thomas’s younger brother, Henry Wryneck, who became the third earl of Lancaster.

The second is that it was in the years the de Lacy estates, including Ightenhill, were property of Edward II that he came to Ightenhill to see them. This was in 1323, the year after the battle of Boroughbridge. The visit might have been occasioned by the battle itself but it is more likely Edward came to Ightenhill to assess the situation in the north-west of England at the time.

The incursions into England by the Scots, since Bannockburn, had not ceased. Scottish armies enjoyed the freedom of the English border counties, something even Earl Thomas had failed to stop. It was at this time that Salmesbury Hall, near Preston, was destroyed by Scottish soldiers who had advanced into England as far as the Ribble estuary. Not only that but civil order had broken down in parts of Lancashire. Edward will have been interested in all of this and Ightenhill was an ideal vantage point from which to assess what was going on.