The greatest of the de Lacy lords

Edmund was born in 1230. This means he would have been about 10 when John died. Edmund would have reached his majority in 1251. In other words, he should, in normal circumstances, have succeeded to his inheritance seven years before he died, in 1258. What happened, apparently, was that Edmund’s mother, who had brought the Lincoln title to her husband, kept it in her own lifetime. As she outlived her son, Edmund did not succeed to Lincoln but he did so to a number of other titles.

That is now clarified, I think. I am always pleased for people to contact me about the articles I write. This correspondent has been very helpful. I had wondered how old Edmund was at death as, if he was over 21, he would have succeeded to all of the estates to which he was entitled. The important thing is, though, that Edmund had an heir, Henry, who was born in 1249, and was to become the greatest of the de Lacy lords.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was not only that Henry was an important national figure, a friend and confidant of Edward I, a soldier and statesman, but the third, and as it transpired, last of the de Lacy earls of Lincoln, was also an important figure to us in Burnley. The Manor of Ightenhill may have been one of the least of Earl Henry’s estates. We do not know whether he ever visited it but we do know he did not put Ightenhill to the back of his mind.

One of the most important things Henry did for our part of the world was to prevail on Edward I to grant a charter for a market and fair to be held in Burnley. The earl had also included Pontefract in the same application which was granted in 1294. Similarly, it was Henry who, only a few years before, had built the first corn and fulling mills in Burnley, stimulating agriculture and the wool industry. In fact, it could be argued Henry was the founder of two of Burnley’s more important industries, a surprise, maybe, to those of you who did not realise Burnley was an important milling town up to the 20th Century, and that, once, Burnley was a centre of the wool, rather than the cotton, industry.

Of course these investments in Burnley, because that is what they were, were intended to make a profit for the Lord of the Manor. The market and fair would produce stallage, a sales tax, and, hopefully at least, there would have been rents to collect from those who operated the mills. We know, for example, the corn mill was much more valuable than the fulling mill, both of which were built on the banks of the River Brun.

Earl Henry made another decision which was significant for the Manor of Ightenhill in that he granted, out of the manor, the Township of Worsthorne to his steward, Oliver de Stansfield who had served as Constable of Pontefract, Henry’s great castle in Yorkshire. By this act Henry effectively created the Manor of Worsthorne, the manor house of which was at Heasandford House. This will be another surprise to those of you who think Rowley was the manor house. After all, that building was actually in the Township, whereas Heasandford, at this time, was in Briercliffe!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCliviger was the scene of similar action by the earl. Here, Henry created a manor from the monastic grange in the east of the township. In 1287 the Abbot of Kirkstall, which owned the grange (a detached farm), was in financial difficulties. It had been founded by Henry’s de Lacy ancestors and now the abbot turned to the earl asking for help. In return for assistance, Henry took the grange into the Manor of Ightenhill but also took the opportunity to regularise his estates in Cliviger by advancing the status of the de la Leghs (ancestors of the Towneleys) and the Middlemores, who also had land from the earl in the western part of the Township. It may be that Henry had plans to exploit the ironstone found on land occupied by the grange?

Something else Henry did affected Whalley which, though it was not in the Manor of Ightenhill, had huge effect on this area. Whalley already had a considerable history as a religious centre. The Parish Church for a large part of North-east Lancashire, including Burnley, was to be found there but Henry decided to allow Stanlaw Abbey, which had been founded by his ancestor, John FitzRichard, lord of Hulton, to move to Whalley. This took place when one of Henry’s aged relatives, Peter of Chester, died in 1296 and the site became available.

Whalley grew into the second largest monastic house, after Furness, in Lancashire. It was from Whalley that its large estates were administered. From 1296, Whalley was not only a more important religious centre, it became a significant centre for business. The Cistercians, the Order at the abbey, were great traders, especially in wool, though their activities encouraged trade in a whole range of commodities.

This actually, and perhaps this is a surprise too, caused problems not only for Whalley, which is built on the Calder, but also for the more established abbey at Salley (Sawley), on the banks of the Ribble. It was not that the waters of the two rivers was the problem, it was that the abbeys were too close to each other. They were competing for the same business and, at times, there not being enough of it, and both houses suffered. A plan for Whalley to move to Toxteth, near Liverpool, where it owned property, was mooted in the 14th Century but, fortunately, for Whalley, the move was shelved.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEarl Henry was a very significant national figure. He was fortunate that King Edward I was occupying the throne of England at the time. Henry and Edward were similar characters, both soldiers and statesmen, and the latter knew he could trust the former. The men were great friends and it could be that, though Edward was the older, having been born in 1239, they knew each other from the times Henry spent at court during his minority. Henry had been brought up at the Queen’s house.

John Harland, editor of “Three Lancashire Documents of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries”, makes the point that Henry was active on the king’s part from the beginning of the reign. He mentions Henry’s taking, in 1273, of the castle of Chartley in Staffordshire for the Crown as an example, but then, unhelpfully, remains silent about the earl’s activities until 1290 when he was appointed first commissioner for rectifying legal abuses which had crept into the judicial system. It was these reforms that created the three divisions of the legal system, the King’s Bench, the Court of Common Pleas and the Court of the Exchequer.

In 1293 Henry was appointed ambassador to the French Court with the difficult task of demanding restitution for French attacks on English merchants and, when Edmund Crouchback, the younger brother of the king, died in 1296, Henry was appointed commander-in-chief of the English army in Gascony and Viceroy of Aquitaine. He enjoyed a significant military victory against the French in 1297 when he raised the siege of St Catherine at Toulouse and expelled the French from the area.

A year later, Henry joined the king in Scotland where he was commander of the vanguard at the battle of Falkirk in which William Wallace was defeated. Henry, therefore, played a significant role in Edward’s wars in Scotland and, in 1307, Henry was appointed one of the two commissioners to open the Parliament of Carlisle and, at this time, took precedence over all the peers of England with the exception of Prince Edward.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

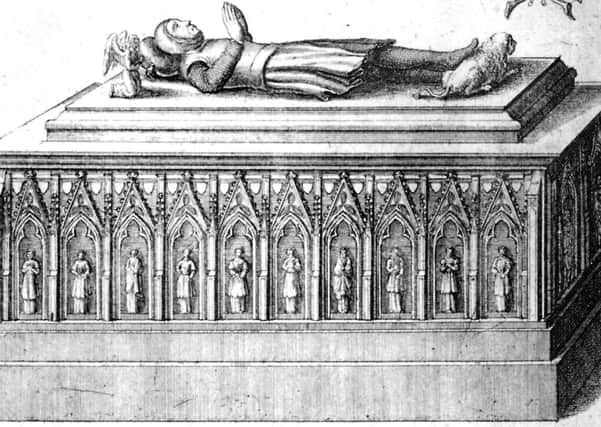

Hide AdShortly after the Parliament, Edward died and Henry became one of the main advisers of the new king, Edward II, but Henry, himself, died in 1310 leaving no heir. He had had four children by his wife, Alice (or Margaret) the daughter of Sir William Longspee, who was a relation of the royal family.

Henry’s two sons, Edmund and John, both died in accidents, probably at Denbigh and Pontefract Castles. The incident at Denbigh, the probable scene of the death of the older boy, has been told as if the accident took place at the Manor House in Ightenhill. Edmund died when he fell into a well and drowned.

The loss of the two boys, and his friend, the king, must have been heavy blows for the earl. He, however, arranged that his only surviving daughter should inherit the title and his estates and pass then to her son, if she had one.