Life at Ightenhill’s old manor house

At one time the Manor House, along with the church at St Peter’s, in Burnley, was the most important building in the area.

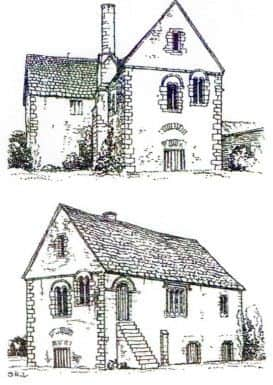

We have already considered what the building might have looked like and have examined how land around the manor, the Lord’s Demesne, was used from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern period when the Ightenhill we now know was established. Today I am going to look at the role of the manor of Ightenhill in local government and judicial systems of the day.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, before I do that, I want to remind you about why I have put these articles together. Ightenhill Parish Council, with the local community, has been successful with a Heritage Lottery Bid. Almost £30,000 has been awarded for archaeological and interpretative works at the site of the manor house which is in the ownership of the parish council.

Work is in hand to improve access to the site and a team of archaeologists will be on site in the summer. They will not be doing any invasive work but have been restricted to undertaking resistivity tests which will determine the extent of the buildings which were reported to be in a ruinous state as long ago as 1523.

Fortunately, the site has never been built on and, just as importantly, a number of authorities have, over the years, visited the site and described what they have seen.

The parish council has this information at its disposal but it needs to determine what actually is under ground so the site can be reconstructed by the artists of Burnley Council’s Graphics Unit.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Graphics Unit put forward the idea that a working model of the manor house might be constructed and put on display so local people will be able to see more clearly what the building looked like and how it operated. This has been accepted and, soon, we will have a community written history of the manor house and its demesne.

Referring to the demesne, I have been asked, by several readers, how the demesne

at Ightenhill relates to the demesne at Huntroyde. The answer is that the word “demesne”, derived from the French “demeine”, mostly refers to the land of a manor reserved for the use of the Lord. Otherwise the word means “the holding of land as one’s own property”. This is the case at Huntroyde where the demesne coincides with the park surrounding the house. However, the demesne at Huntroyde is not manorial - it is literally the part of the estate which was set aside for the use of the landowners. In this instance the demesne became a private park with walks through the gardens and woodland. There were also several fish ponds in the grounds.

Any study of a manor must start with its Lord. Every Manor had a manorial lord, the owner of the manor under the Crown. In the case of Ightenhill, its lords were the de Lacy family, who were also Lords of the Honors of Clitheroe and Pontefract.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn Honor usually contained a number of manors. Clitheroe, for instance, contained Ightenhill, Colne and Accrington and other manors.

The first of the family to have a connection with Ightenhill was Robert de Lacy who did not hold the estates very long as he was a supporter of a rebellion against Henry I. By 1115 the land was in the hands of Hugh de la Val, who is mentioned in our local history because it was he who, in 1120, granted the churches of Burnley, Clitheroe and Colne to Pontefract Priory.

The next Lord of the Manor was William Maltravers, who was murdered. The whole of the estate, of which Ightenhill was only part, was then restored to the de Lacy’s in the person of Ilbert de Lacy. He was the first of seven de Lacys to continuously hold the estates from 1135 to 1311. The heads of the family were Barons until John de Lacy (d1240) was created Earl of Lincoln.

The third of the earls, Henry, petitioned Edward I for permission to set up a market in Burnley but when he died, in 1311, the estates passed, by marriage, to Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, a cousin of Edward II. Thus the earldoms of Lancaster and Lincoln were combined in one man who became leader of a bid to oust the king. This failed at the battle of Boroughbridge in 1322 and it was after the battle the victorious king made his one and only visit to Ightenhill.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThomas was executed and his estates, including Ightenhill, became the property of the Crown, so when, in 1323, Edward II visited his manor house at Ightenhill he did so as Lord of the Manor, Earl of Lancaster and also as King.

The Lancaster and Lincoln estates remained in the possession of a member of the royal family, but not the Crown, until 1399. In that year Henry Bolingbrook, son and heir of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, seized the Crown from Richard II and made himself Henry IV. From then on, to the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, the manor was in the hands of the Crown, a fact which has a marked bearing on our local history, one to which I will refer in another article.

Of course, neither the de Lacys, nor the Crown, could administer the manor directly.

As we are about to see, the manor was responsible for a number of activities – the running of the demesne and administration of the commons, wastes and woodland of the townships of the manor. The manor also had a legal role in running its own courts. These related to farming tenancies, settling disputes between tenants and even included determination of how land in the townships should be managed. The manor also had a considerable role in local government, in interpreting laws of the land and in enforcing local bye-laws that related to the manor. I have mentioned the Bye Laws of Extwistle, which were manorial and related to land use, in a previous article.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe should start with the courts which were properly known as Halmote Courts, the courts held in the hall of the manor house. In most manors there were two courts, the Court Baron and the Court Leet. One dealt with land issues, such as succession to copyhold properties and the resolution of disputes about how land should be managed. The other court was more general but was concerned largely with crimes and civil offences.

When the Halmote met at Ightenhill the great hall of the manor house was prepared. The steward, usually a great man like Sir Edward Stanley, who was assisted by a jury, presided in the place of the Lord of the Manor and cases were presented to them by the Greave, the active official of the manor. The Greave was something like a chief executive and the cases he presented to the court had already been extensively researched. Usually, the accused were declared guilty but there are examples of cases where the Halmote failed to make a decision and other courses of action were taken. These included long and very thorough inquiries and the sending of some cases to higher courts for determination.

There a few things that should be pointed out. One is that all residents of the manor, who achieved a particular status, had to attend the Halmote when they were called. Juries were elected from those who attended and they, too, had to serve, whether they liked it or not. If those called and/or elected did not attend they were fined if they did not have a good excuse.

Another observation I would make is that everyone, regardless of station in life, was responsible for bringing malefactors to the Halmote. This, in part, explains “hue and cry” incidents of the past when all the local populace would join in the hunt for a declared criminal, the very British, and much older, equivalent of the American “possee” which was a standard feature of a Western. I have often wondered if victims of British “hue and cries” met the same fate as many of their American cousins, ie hanging from a lonely tree!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe manor was also responsible for local administration. This was done through the appointment of officials who worked with the Greave. Each township in the manor had to have a constable, who may then have appointed an assistant constable to actually carry out the work, which was quite onerous. A constable had his normal duties associated with keeping the peace, but he was also responsible for the collection of manorial fines and it was he who carried out the wishes of the court when it came to a criminal being placed in the stocks, whipped at the whipping post or subjected to the tender mercies of the ducking stool.

Burnley had one each of these and there was also a place in which to keep miscreants though we know little about it for the early years of manorial administration. The constable also worked with the ale taster, pinder and hedge layer. The first of these did what the job description said and there are numerous cases of Burnley inn keepers producing bad ale. It was the constable’s job to collect the fines after a court decision and to ensure anyone who made ale, and intended to sell it, should have a licence.

The pinder essentially looked after sheep and cattle of the district. There was a pinfold in Ightenhill, as there was in all of the townships of the manor. However, none of them have survived in Burnley but you do not need to travel far to see two examples, for pinfolds have been preserved at Higham, which was in the manor of Ightenhill, and Waddington. Both are excellent examples and well worth a visit.

The hedge-layer’s job was a particularly important one. People were obsessed by boundaries. It was important boundaries should be marked and though there were many means by which this could be done, it was the quick thorn hedge that was chosen in Burnley. “Quick thorn” is a phrase descriptive of both the hawthorn, the most common of our smaller trees even today, and black thorn. This latter is the plant which produces the fruit known as the sloe and I have every reason to believe this year is going to be a great year for sloes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJust look for the hedge or small tree on which the flowers appear before the leaves. That is usually a black thorn, mark the location in your mind, keep an eye on it and return in autumn.

We know quick thorn hedges existed in Ightenhill and I suspect the first boundaries round Hapton and Towneley Parks were hedges. To be precise, I feel they would have been hedges situated on mounds created by the making of ditches. It is likely boundaries around woodland would have been of hedges and it may be the case that hedges would have, at one time, formed the boundaries between the open fields of the township of Burnley.

I know there are other things I could have written about with regard to the Manor of Ightenhill. For instance, I have not mentioned details of any of the Halmote Court cases so I will probably return to this in future. Some of them make interesting reading. By the 1440s Halmote Courts were being held in St Peter’s Church and the manor house, its great hall, chapel, kitchens and stables, along with the Greave’s house, were in ruins by 1523. The work that is about to start at Ightenhill will tell us much more.

I’m looking forward to it and I will keep you informed.