Following in the footsteps of medieval kings

Ightenhill Park Lane is the proper name for the one many locals use: Park Lane. However, both of these names are relatively recent as this highway is undoubtedly one of the oldest in the Burnley area. Let me quote from “Leading the Way: A History of Lancashire’s Roads”: “John of Gaunt, when visiting Ightenhill near Burnley (probably to check on his equicium or stud there, rather than for the hunting as Goodman suggests) would have used the “king’s highway” not a wain-gate.”

In medieval times a wain-gate was a wagon route, often an important road but lacking the high status traffic of a king’s highway. John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, was Edward III’s fourth son.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe died in 1398, the year before his son, Henry of Bolingbrook, who had been banished from England by King Richard II, seized the throne as Henry IV.

I have mentioned, often in my articles, that when Henry IV succeeded to the throne, Ightenhill and Burnley, for that matter, became royal possessions. This was because Henry IV came into possession of the lands formerly in the ownership of his father. One of these was the Manor of Ightenhill. Duke John had also been possessed of the Lordship of Clitheroe, and its castle there, and was even the owner of the corn and fulling mills in Burnley.

All this property, and much more, came to the Crown as part of the Duchy of Lancaster and, as you will know, the Queen, and all monarchs since 1399, have been Dukes of Lancaster, whether male or female. This applied to Mary I, Elizabeth I, Mary II, Queen Anne and Queen Victoria.

About 1399, the Burnley Soke Mill, the old name for Burnley’s corn mill, changed its name to the King’s Corn Mill, later shortened to King’s Mill, as it was owned directly by the Crown. This does not mean the Crown operated the mill. What usually happened was that it was leased to a local family – the Towneleys and Shuttleworths – both held the lease, and sold the right to operate the mill to a miller.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat I have written so far is merely to underline the fact there were reasons for important people to come to Burnley as long ago as the Middle Ages. John of Gaunt, a royal prince, was successor to the de Lacy family which had been granted almost the whole of North-east Lancashire, later known as the Lordship of Clitheroe, probably in the reign of William Rufus, the son of William I, who came to the throne in 1087.

Their main base, in the north of England, was in Yorkshire at the great castle of Pontefract. This castle commanded the important road from the south of England to the North East and, from there, to Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, which was a separate country until the Act of Union in 1707. But there was another road which started at Pontefract and made its way to the west and to the part of the country we now know as Lancashire though it was not until 1182 that the term “county of Lancaster” was in use.

Apart from a small number of south to north roads, of which the Great North Road, the one which passes through Pontefract, was the most important, it seems the majority of the remaining roads in North-east Lancashire, and the West Riding, were west to east.

It might be unpalatable to present day Lancastrians but, in the Middle Ages, Yorkshire was the dominant county. When the Domesday Book was compiled, in 1086, there was no section for Lancashire. Much of what we know as Lancashire was included in the Cheshire section or as part of the book which comprised Yorkshire, the Lune Valley and much of the Lake District.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI have mentioned that the Lords of Pontefract needed to get to their large Lancashire estates based on the castle at Clitheroe but we should add to this that the most significant ports in the north of England, in an age when most trade was with continental Europe, were on the east coast and some of them, like Kingston-upon-Hull, were in Yorkshire.

We can go further in that Yorkshire had great influence over the west of the Pennines when it comes to religion. Not only were a number of Lancashire’s monastic institutions founded by Yorkshire families, York had an archbishop whose responsibilities included Lancashire which was without a bishop until the 19th Century. Cheshire only got a cathedral in the reign of Henry VIII. He made Chester a diocese in 1540.

The route from the castle at Pontefract to the one at Clitheroe has long interested me. I have tried to work it out but have not succeeded and, if you know the road maps of the area between the two towns, you will see what I mean. In the years since this route was instigated, the element of the traffic flow that was east–west has become dominated by a south–north flow, which, as you will recall, was present at the Pontefract end in the early days.

What I suspect was the case is that parties travelling from Pontefract to Clitheroe would have come through Burnley. The present road from Todmorden to Burnley is a much later turnpike but there is an ancient road which covers a similar route, though it is not from Todmorden, it is from Hebden Bridge.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOf course Hebden Bridge is not an ancient place but the road to which I make reference starts near that town and heads for Burnley. This is the Long Causeway which I have seen referred to as, perhaps, dating from pre-Norman times.

A causeway is a term which describes a maintained road. It can, of course, refer to a “causey”, a narrow, stone-lined route designed for pack horses but that is not always the case. It seems to me the Long Causeway would have been a king’s highway like the one I mentioned when referring to John of Gaunt.

After passing through Burnley, originally through Towneley Park, the road made its way, above Burnley to Habergham, possibly joining the old Sandygate in the Gannow area. From there the road got to what is now Ightenhill Park Lane which was the quickest route, and possibly the least dangerous one, not only to the manor house at Ightenhill, but through the ford and over the stepping stones on the Calder to Higham.

This latter place, to some extent, succeeded to some of the manorial responsibilities of Ightenhill. An important court was held at Higham though it was mainly involved in the administration of the Forest Laws. From Higham there were several alternative routes to Clitheroe, and, from there (or near there) there was a route to Lancaster through Bowland, the same route the witches of Pendle took on their way to their trial at the great castle of Lancaster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

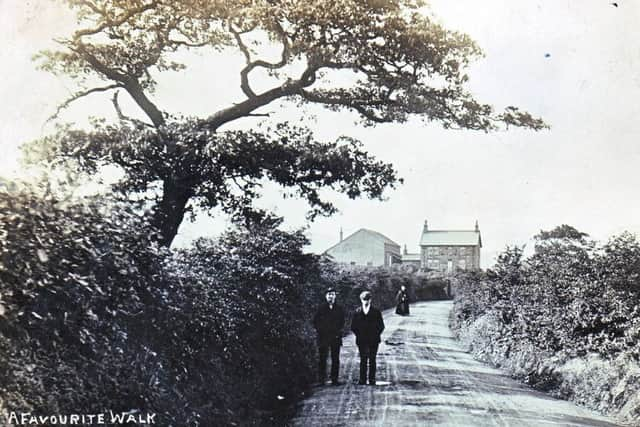

Hide AdWhat was Ightenhill Park Lane like in the days before houses were constructed along its length? We do know quite a lot about this for the later medieval period. There was the Manor House until the early 16th Century where there was also a chapel, a blacksmith’s shop, a barn and at least two other houses. Ightenhill, the place, is properly “Ightenhill Park”, and until about 1340, much of the land was given over to hunting and the rearing of horses – that is where John of Gaunt’s equicium comes in.

In later years, the Park, divided up, became the home of a number of scattered, mainly pastoral farms, some of which have survived to today. It may have been for them that the pinfold, which is known to have existed on the Lane, was built, but I suspect there would have been a pinfold in the area many years before that. Sheep, and the wool they produced, were significant even in the Middle Ages.

The one constant feature of Ightenhill Park Lane, for much of its history, was the ford (and the stepping stones adjacent to it) where the lane meets the Calder. The stepping stones have the more visual impact so people know about the stones. What they do not realise is that the ford, slightly down stream, and still discernible, was the more important.

And, after, negotiating the ford, we are in Pendle but I recommend that, if you are in the area, walk the route of the ancient lane to Higham. You can still do it and, with the help of a former colleague, I will be your guide to this walk in a future article.