Corn mills ... how we came to have ‘stew and hard’

I concentrated on the mills which once existed in the current borough of Burnley but mentioned mills in other nearby boroughs where appropriate.

In addition, I outlined how the individual premises had been used. Most had been built as corn mills though some were converted later in their existence to other uses, wool and cotton spinning and weaving, for instance.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOthers had been designed for fulling (a process in the wool textile industry) and that one, in Cliviger, had been built as a blast furnace for the iron industry but on the site of a former lead smelting mill.

It was the corn mills that interested me most. A number of people have contacted me about the article sharing with me my surprise that an area not known for its arable farming should have had so many corn mills.

Other readers wanted more details about King’s Corn Mill, Burnley’s oldest, the site of which is not marked though the little roundabout between Bankfield and Edward Street, in the town centre, is probably where the mill was located.

It is the intention of this article to consider the first of these subjects: why there were so many corn mills in the area.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe story of the King’s Corn Mill itself will be considered next week and, in that article, if I have space, I will look at later mills, particularly those in Burnley itself, and why it was that an inland town, some distance from a recognised corn growing area, could have become the important centre of milling that Burnley became in the 19th Century.

The milling of corn is one of our oldest industries. Before the coming of powered mills, corn was ground in hand-operated stone querns, the remains of a number of which have been found locally. Incidentally, in Britain the word “corn” is inclusive of wheat, oats and barley, but, in America, the word is reserved for what we call maize. Your corn-flakes are made out of maize, not wheat, and, though some maize is grown here, it is not a traditional British crop.

There were early corn mills in Burnley, Extwistle (2), Cliviger, Padiham, Read, Whalley, Great Marsden and Colne. At a later date there were additional Burnley corn mills at Basket Street, Pillingfield, Gannow and Hill Top, a remarkable number when it is considered Burnley is not in a grain growing area.

There are a number of reasons why Burnley is not now noted for producing wheat, oats or barley. One of them is to do with the relatively short growing season in this part of the Pennines. Wheat and barley take longer to ripen than oats. Our short and relatively cold summers are often just not capable of ripening the former though oats often come to fruition in our climate.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis might explain why, until recent times, oat cake was so important in East Lancashire and West Yorkshire.

How many of you remember that local delicacy “stew and hard”? The “hard” was oatcake which was the staple of this part of the country right up to the mid-19th Century.

In fact the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, which was raised just over the border in the valley of the Yorkshire Calder, was known as the “Havercake Regiment”, the regiment that ate oatcakes!

In most of our towns and villages, until the early 20th Century, there were numerous specialist firms – often of one or two people – making oatcakes in tiny bake houses. When I was a boy many corner shops sold “stew and hard” and a frequent visitor to the Market Hall and old Open Market, there were stalls where you could get great “stew and hard”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese days Staffordshire seems to have cornered the market for oatcake nostalgia but North-East Lancashire’s claim is just as good and perhaps we should revive it at Queen Street Mill Museum, Harle Syke.

Wheat and barley, if they were grown, often needed treatment before they were milled. This was applied in a corn kiln one of which has survived at Winewall, near Colne. Corn kilns were integral to most of the corn mills in our part of the world but, until recently, I did not know what they looked like, nor did I know how they worked. Visits to Heron Mill, near Beetham, north of Morecambe, and Gleaston Mill, near Ulverston, both places very well worth a visit, have resolved these problems.

Corn kilns dried the grain making it possible for it to be milled. Without such treatment a sticky paste, useless for making into bread, would have been produced in the mill rather than the flour desired.

However, we ought to ask the question, was there ever a time (in North-East Lancashire) when a corn kiln might not have been needed? If that was the case, that might explain why there were so many mills at such an early date as, say, the early 14th Century when we know there were mills in Burnley, Padiham and Colne.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe climate of the north Atlantic is subject to change. According to NASA the period 1550 to 1850 is known, over this vast area which includes Europe and North America, as the “Little Ice Age”. This does not mean the North Atlantic was covered by an ice sheet but the climate was colder than it had been and cooler than it is at the moment. NASA identifies three years as being particularly cold, 1650, 1770 and 1850, ones in which crops failed.

If we look at an earlier period we find the years 950AD to 1250 are known as the “Medieval Climatic Anomaly”, otherwise the “Medieval Warm Period”. The latter date is suitably close to 1290 when the first mention is made of the earliest corn mill in Burnley, and note that 1290 is the year when the building is first recorded – it is likely the mill was older.

Similarly, another very old mill was the monastic mill at Extwistle. We know it can be traced to the 1320s but the abbey at Newbo, Lincolnshire, was gifted the land on which the mill stood about 1190. It could be that a mill was built in Extwistle nearer the date when the property was acquired and the same is possible for a number of other mills, like the ones in Colne and Cliviger.

If the climate was better in the early period, and there is little reason to doubt it was, it could be that the growing of grain crops was more attractive than it became later. Mr Bennett, in his “History of Burnley” Volume 1, gives interesting figures about the revenue of the Burnley corn mill. He states in 1296 the revenue was £10 per annum but by 1311 it had dropped to £5 and that, though there was a recovery in succeeding years, it was only at £5 4s 0d (£5.20) in 1400 and £3 7s 4d (£3.36) in 1440.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMr Bennett does not refer to a “Medieval Warm Period” though he does speculate there might have been some change in the weather. He does refer to poor soil, exhaustion of land and lack of manure caused by disease in cattle. Of course, all of these might have contributed to the problems faced by Burnley’s miller but the coming of colder times (some speculate the evidence points to an earlier date, c1350) looks convincing to me.

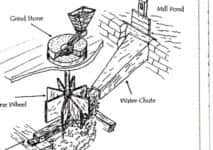

Burnley did not have the status of a Manor. It was a Township within the Manor of Ightenhill but Burnley, by 1290, if not before, was home to the manorial corn mill and it also, at the same time, had a smaller, but still significant, fulling mill. The mills were both run under manorial rules and were only a couple of hundred yards apart. They were both water powered, taking their water from the Brun, a system which can still be identified today.

In the earlier medieval period the climate might have been better – less rainfall, warmer – but there was enough water to drive both mills. The catchment area of the Brun is quite extensive, taking in the Don and Swinden Water together with numerous smaller streams. If the monastic mill at Extwistle, which is on the right bank of Swinden Water, could operate efficiently until 1537, when we last hear of it, then Burnley’s manorial mill, situated lower down the system, could operate with similar, if not greater, efficiency.

That these mills, and others, operated is beyond doubt.

A corn mill, especially in the earlier period, was essential to the well-being of any community.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe thought occurs to me that, though life itself might just about have been possible without a mill, it would not have been possible to make bread and, (just think of it!) similarly, it would have been impossible to brew beer! In those circumstances, one might ask about whether life would have been worth living!

In later years there are references to a larger number of Burnley corn mills “importing” corn from other areas, especially Yorkshire, but, for most of the time from 1290 to the modern period, transport costs were too high for this to take place on a large scale.

Burnley was also inconvenienced by not being on a navigable river where the movement of bulky goods was easier and cheaper than by road. In these circumstances there was a need for grain to be grown locally whether the climate was conducive or not.

The coming of corn kilns, possibly to some extent a consequence of the “Little Ice Age”, is another factor in the story and one which, although there is plenty of evidence around us even today, has not been fully explained.

In future articles I will look at this but, next week, I will tell the story of Burnley’s King’s Corn Mill and try to recreate what it looked like.