Ralph never forgot the sinking of the Svenner

Blacko veteran Ralph Woolnough saw the predator strike again less than six weeks later when it ripped a British warship in two.

It was June 6th, 1944, otherwise known as D-Day, a sea and air attack on Normandy’s beaches, with the aim of liberating France from German control. Code-named Operation Overlord, it saw allied British, US, Canadian and French forces land on assault zones named Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

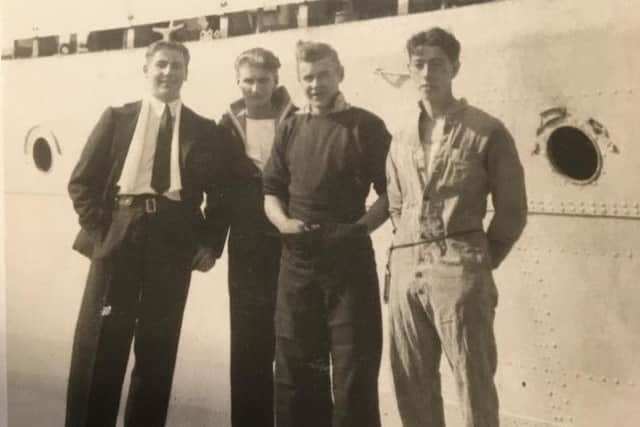

Hide AdNineteen-year-old Ralph had given up a scholarship place at Cambridge University to join the Royal Navy and serve at D-Day.

“Next to us was a Norwegian destroyer, the Svenner, and I had a grandstand view when she was hit and broke in half,” he said in his unpublished memoirs written before his death in January at 93 years old.

“She’d been torpedoed by E-boats coming at her from the other side. There were 34 killed and 15 wounded.”

The Nazi Enemy boat, also called the S-Boot or German Schnellboot, had two powerful torpedoes and was difficult to spot without radar.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt wreaked havoc at a D-Day practice named Operation Easy Tiger, near Slapton Sands on April 28th. Just after midnight, the Germans heard the buzz of radio and shot across the Channel.

The E-boat sank two US vessels, and damaged a third, killing at least 749 people.

Easy Tiger was a dry run for the Utah Beach landings and caused more than three times as many fatalities as the real thing.

Ralph, who sailed for Normandy at 20-years-old, had been a seaman on a County Class Cruiser during the Christmas of 1943.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was one of the ships at anchor in Scapa Flow which cheered the Fleet back in after the Battle of the North Cape and the sinking of the Scharnhorst,” he said.

The Battle of North Cape began when British intelligence baited Nazi battle-cruiser Scharnhorst from its base in Altenfjord, Norway, on Christmas Day, 1943, after intercepting German signals. British ships torpedoed it, killing 1,927 German soldiers, with only 36 survivors.

“I left Scapa Flow on New Year’s Eve, and crossed the Pentland Firth in a gale on a ferry carrying the German survivors,” Ralph said.

“The rail journey afterwards from Thurso down to London took about 36 hours. It wasn’t the best New Year I’ve ever had, but I was better off than the poor prisoners.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe then joined the refitted HMS Kelvin, a 1700 ton destroyer, down in Chatham.

“It was one of only two out of the 16 J and K Class boats to actually survive the war.

“The most famous was the Kelly, commanded by Lord Louis Mountbatten, who was the sort of barmpot who went round looking for trouble and was always getting damaged as a result. These people are necessary in wartime but best avoided if you want to live to a ripe old age.”

He was then sent back to Scapa Flow, Scotland.

“The weather was still awful: sleet and snow,” he said. “Most of the rest of the fleet was also up there, hidden away to stop the Germans suspecting an invasion force was being assembled. The weather improved by the hour when we left Scapa.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The evening before D-Day the harbour was chock-a-block. I remember hearing bagpipes across the water.

“It was Lord Lovat’s Highlanders going aboard. The piper was to lead them back ashore on to the French beaches many hours later. Before sailing we had an All Hands On Deck speech from the captain who said that his orders were to beach the ship if we got hit, and to carry on firing.”

Ralph didn’t land at any beach and instead served at the port with an Oerlikon gun crew, heaving ammo and shelling the enemy.

“As it started to grow light we got our first view of hundreds of ships stretching to the horizon on all sides.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat’s when he saw the sinking of the British HNoMS Svenner off Sword. The German 5th T Flotilla had seized the coastal town of Le Havre and fortified it with artillery. Securing firing range, an E-boat launched two torpedoes at the S-class destroyer, which exploded before being devoured by the sea.

“The two ends came up out of the water in a V, she disappeared quickly, and the rest of us sailed on,” he said.

“She had the unfortunate distinction of being the only ship to be sunk by German naval action on D-Day. It could have been us on the Kelvin: we were next in line and close enough.”

Its anchor was recovered 59 years later by the French Navy and created The Svenner Memorial at Sword Beach.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDemobbed at 21-years-old, Ralph worked in the textiles industry, becoming a manager of Bannister Mill in Colne in the 1950s.

In 1951, he married his wife Margaret, a teacher at Colne’s Lord Street Primary School from the 1950s to 80s.

The couple moved to Blacko in 1968 where Ralph joined the parish council and carried out a village appraisal. He was also instrumental in turning an old police station into housing.

“It’s all luck,” he added. “Over 70 years later I’m sitting comfortably and typing this, but some Norwegian lads never saw home again.”