Our local links with Skipton Castle's turbulent past

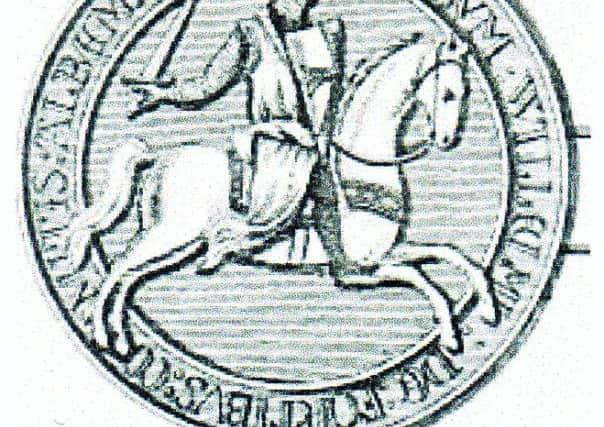

John “took the Cross” in 1214 and later travelled to Damietta in Egypt and took part, with Ranulf, Earl of Chester, in the Fifth Crusade. By 1220 John was back in England, a country which he found was sliding back into yet another civil war.

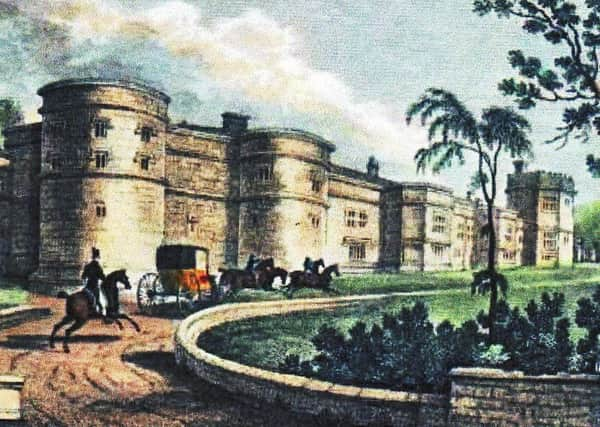

Walter Bennett, the historian of Burnley, introduces the incident we are going to examine in the following way. “Early in the reign of Henry III he (John de Lacy) went to the Holy Land, and on his return attacked and captured for the king, Skipton Castle, the stronghold of a rebel lord”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen I first became familiar with Bennett’s “History of Burnley” I wondered what the incident at Skipton might have been about, who this rebel baron might have been and what were his grievances? To my young mind it seemed there was the possibility of a romantic siege or, better still, a gory one, or, perhaps, a pitched battle, somewhere beneath the castle walls in Skipton. Could it be that Burnley men had taken part?

I soon found that none of the books I had at my disposal made mention of John de Lacy’s attack on Skipton Castle. It was not until my university days, at Manchester, that I came across (by accident) a source which, admittedly in an oblique sort of way, referred to a northern rebellion against the Regency which governed England during the minority of Henry III. Years later, when Timothy, my youngest brother, was living in Cockermouth I read about the siege of Cockermouth Castle which also took place in 1221.

It had taken years to formulate, but a picture of something akin to a civil war, or possibly a rebellion, at the time of Henry III was coming together in my mind. However, it was not until I started in earnest on the Ightenhill Manor House Project, which concluded last year, that I resolved the mystery.

I am now in a position to put flesh on the bones and think you will find it worthwhile. I ought to add that a fuller version of what you are about to read will appear in a forthcoming book on the de Lacy family which I have written. I will let you know when it is published.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe sealing of Magna Carta in 1215 did not bring an end to the dispute between King John and his barons. In fact, the king contacted the Pope who annulled the agreement ruling that, as it had been “signed” under duress, it was not valid. An insurrection against King John had already started in the north of England. This quickly spread to the rest of the country and its leaders invited Prince Louis, heir to the French throne, to join them with the promise of the English throne when they were successful against the king.

John died in 1216 and was succeeded by his nine-year-old son, Henry III. He was, of course, too young to rule. A Regency was, therefore, set up under one of the great men of English history, William the Marshal. William was assisted by Ranulf, the Earl of Chester, and they were spectacularly successful in defeating the rebel barons at the battles of Lincoln Field and Sandwich in 1217. The former was a bloody affair but Sandwich was the first great English naval victory, one of many the English were to enjoy, over the years, against the French.

For their part the French, defeated, returned almost empty-handed to France, but the situation in England was not resolved. The death, in 1219, of the wise William the Marshall did not help and, in Earl Ranulf’s absence, the Regency fell into the hands of people whose policies perpetuated the rift between the crown and a considerable number of the barons.

Remember the “rebel baron” referred to by Walter Bennett? Well, he was a particularly unpleasant character by the name of William des Forz, Earl of Aumale, and it is he who links Skipton and Cockermouth, as does castles at Skipsea and Scarborough, also in Yorkshire, Bytham in Lincolnshire and Fotheringay in Northamptonshire. All of them were subjected to sieges in 1221 and William des Forz was the man responsible for what happened.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn fact William instigated a rebellion against the government of Henry III. Some historians have called it the War of Bytham but, in my book, I have given it the name of the Aumale Rebellion. John de Lacy was, therefore, commanded by the king to be involved in the almost nationwide measures to put down this rebellion.

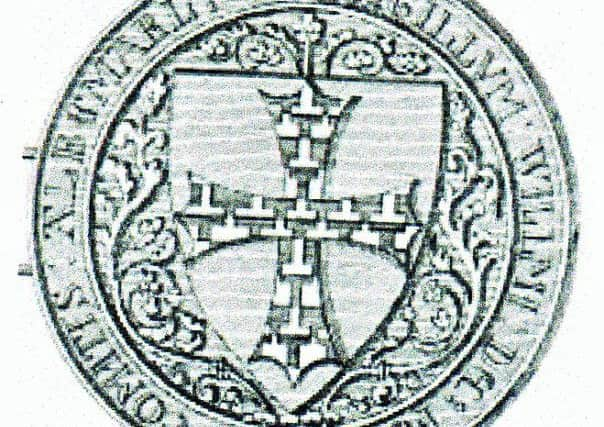

A few words of explanation are needed here. First, why have I used the phrase the “Aumale Rebellion”? William des Forz was the earl of Aumale, but you will not find a place of that name in England. Aumale is a county in Normandy of which some of William’s ancestors were the counts. The English equivalent of a count is an earl and William’s family held the title not from the kings of France but from the kings of England in their capacities as Dukes of Normandy.

You will remember that William, Duke of Normandy, became King of England when he defeated Harold II at Hastings in 1066. He did not give up the Duchy and continued to rule it even though he had become King of England. The Conqueror’s descendants, particularly Henry II, added much more of France to the territories of the kings of England and one of the least significant of them was Fors which, today, is in the Deux-Sevres (Poitou-Charentes region) of South-west France.

It was from Fors that the Earl of Aumale’s family had come. They had acquired the earldom by marriage but not without difficulty. King John was loathe to accept the claims of William des Forz and only did so when, almost at the crisis of his reign at the time of Magna Carta, he thought he could buy his support in the coming war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAumale, as a title, was something of a busted flush in that, since the 1190s, the Norman county of that name had fallen into the hands of the King of France who did not recognise the claims of the English family. Philip of France eventually chose one of his own supporters to fill that role but the title was still recognised by the Kings of England, just as they claimed to be Dukes of Normandy even though the duchy had been lost by King John to the same Philip of France.

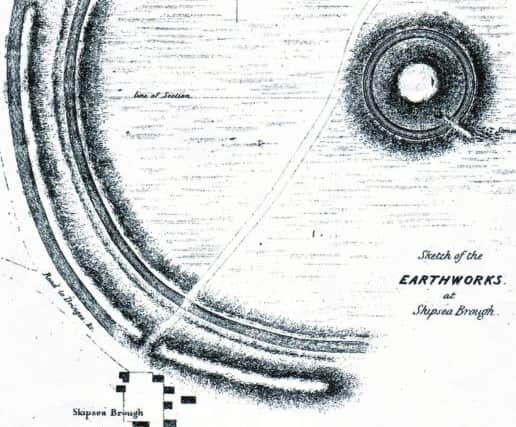

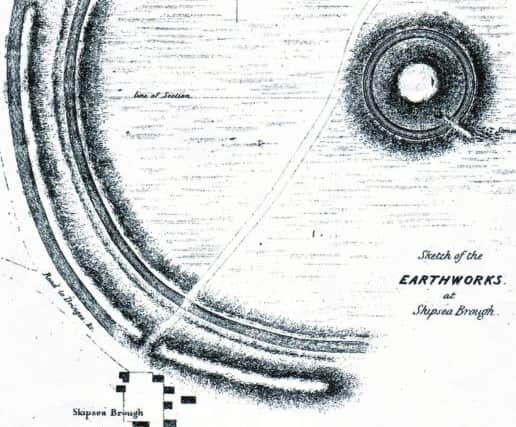

William des Forz was a little peeved, to say the least, that the extensive lands once owned by his family in Normandy had been lost because of the inability of the King of England to defend them. However, he still had extensive estates in England. These were centred on Skipton, Skipsea, Cockermouth and Bytham, but the first three were in a part of the country claimed by both England and Scotland and, at this time, preparations were being made for a peace treaty between the two countries.

William must have looked at the situation and realised it was possible his castles and estates in northern England might be bargained away in the discussions about to take place. His suspicions were aroused, I suspect, when he was chosen as a hostage when the Anglo-Scottish discussions were being planned. Incidentally, at this time, hostages were taken by both sides in situations like this. The practice concentrated the minds of those involved in the discussions, but it was inconvenient for William who, had the worst come to the worst, and his castles in the north of England come into the equation, would have been able to do little about the problem.

There were other reasons why the Earl of Aumale made the decision to rise against the king in 1221.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor example, he had held a tournament at Brackley, Northamptonshire, against the express wishes of the Papal Legate, Pandulph, now acting as Regent. For this he had been declared a traitor and was excommunicated. Perhaps worse than this, at least for his earthly status, he had refused Henry III entry to the royal castle of Rockingham of which William was the castellan.

In a short time William was ordered to vacate both Rockingham and Sauvey (a castle in Leicestershire) and, on being refused, the king incandescent with rage, and young as he was, decided to attack both of them himself. They quickly fell and the king turned his attention to the great castle of Bytham in Lincolnshire. He ordered that it be besieged and, for that, specialist equipment was constructed at great cost and assembled at the castle.

This was a major conflict and both sides had the support of a number of baronial families. Bytham fell to the king and he ordered that it be destroyed. Writing, 300 years later, John Leland, on his famous travels through England, noted, “Two miles from here I saw Bytham Castle, where the substantial walls of the building survive …”. After all those years the royal master, for whom Leland was writing, would have known what had happened there though, these days, we have forgotten about the startling events at Bytham that, at one time, gave the name to Bytham’s War.

After this, William des Forz fled to his estates in the north hoping to reach Skipton Castle but was prevented from getting into the building by his own retainers. They were doubtless aware of what had happened at the three castles in the East Midlands and the south of England and feared what might happen if the king marched against them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe know three of the four castles in the north were attacked. As a royal castle, Scarborough was the exception in the way it was dealt with by the royal host.

We know, also, that John de Lacy was not the only baron called upon to lay siege to Skipton. He was actually ordered to “assist”, a word that implies he was not alone. John was, of course, the owner of great estates, including the one based on Clitheroe, here in Lancashire, and, as such, he might have expected to be involved.

John de Lacy had the military experience for such an expedition and might have planned what he was going to do in Yorkshire at his castle at Clitheroe. Alternatively, he could have undertaken the same exercise at his manor houses in Ightenhill or Colne. Men in his force would have come from our part of the world.

Unfortunately, we have no details of the siege at Skipton itself.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMy childish musings cannot be verified but we do know Skipsea was slighted, and not rebuilt; that Cockermouth was destroyed, but rebuilt and Skipton was partially destroyed and magnificently rebuilt.

The castle at Skipton is one of the glories of the Yorkshire Dales. When next in Skipton take time to visit the castle. When there, think about those few word in Bennett’s “History of Burnley”, John de Lacy and his protagonist, William des Forz. Oh, and what happened to William des Forz? He got Skipton and some of his other castles back, settled down to become a loyal supporter of the king and died on Crusade!