When Burnley led the cotton world

Each article will be constructed around a theme some of which, I feel, will be quite new even to those of you who know about textiles, but I do not intend to forget that Burnley has changed considerably in my lifetime.

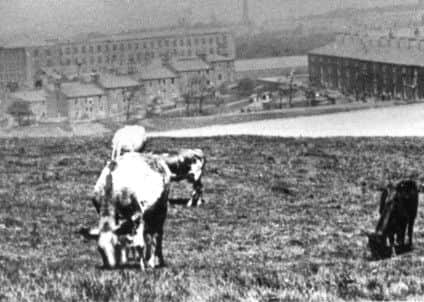

The town was once the most important cotton weaving centre in the world but, though the references to Burnley as an “old cotton town” reappear regularly in the press - as they have done with the recent promotion of our football team to the Premier League - Burnley is no longer engaged in cotton on any large scale.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMany of the people who live here are so disconnected to the cotton industry they do not know the difference between warp and weft, or what a loom’s shuttle or slay might be. They might know what a weaving shed is but would they know there is another shed on the loom?

It might be argued that few people, these days, need to know what these obscure words signify, but there was a time when just about everyone in Burnley was aware of what they meant. They also knew how important the cotton industry was to the town, that something like 70% of the jobs in Burnley’s manufacturing industry were found in its mills and most of the rest, in coal and engineering, were dependent on cotton, perhaps more so than any other town in Lancashire.

I know Burnley’s knowledge about cotton is passing away as are the spinners, weavers and overlookers of old.

This came to my attention when I was teaching at St Theodore’s. I had taken a piece of coal, which I had dug out of the ground at the site of an old coal mine in Haggate, and, when I introduced it to a class of 14-year-olds, only one or two of the boys could tell me what it was and how it was used.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was an eye opener for me, but, as a family, we had burned coal on an open fire and I could remember the noisy and dirty deliveries of huge amounts of coal to the steam-powered mills of my childhood.

Of course, the boys, in a new age of central heating, could not relate to this and most of them were not aware that, in the days before natural gas, that commodity had been made from coal in the local gas works.

The same was true when we talked about textiles. When I told the class Burnley was once famous the world over for its cotton cloth the boys (and there were only boys) were not impressed. This, in turn, made me think of my introduction to the reality that Burnley had been - in fact, was still, at that time - a cotton town. When I found out, and I ought to explain that none of my family worked in cotton, I have to admit I was disappointed. How could people spend their lives making boring cloth when they could be making something useful like a car?

I suppose this might have been the reaction of any small boy. We lived among weavers, were woken up by them every morning as “the clogs”, as we called them, marched from Cobden Street, down Burnley Road to the mills.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSimilarly, we were familiar, not only with the sounds, but also with the sights and smells of the cotton industry.

There was a mill and mill pond (we called it “the lodge”) at the bottom of our little back street and though both of them, in different ways, of course, loomed over our lives there was a disconnect between us and the realities of work. My father was employed in the town hall and he clearly enjoyed his work. My childish mind, therefore, had come to the conclusion everyone enjoyed their work or else why would they do it? However, once it was explained to me, I could not get my head round working within the confines of a deafening weaving shed.

This was brought home to me when I was about three. My mother’s older sister, Aunty Kathleen, had made me a winter coat. Of course this was of little interest to me, but the adults fell over themselves with praise for the garment. I ought to add Aunty Kathleen was very good with a needle; she had made beautiful clothes for herself and her own children.

The material for this creation, which was white as I remember; the stitching; the lining (which had been bought at a mill shop in Burnley) and matching hat, were all, according to the adults, wonders of creation, but all I wanted to do was get out on the back street and play with my beloved Dinky toys (all cars and buses, of course)! My view (erroneous as I found out later) was that cotton had no connection with cars and was, consequently, not worth very much attention.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs I grew older my attitude to cotton changed. I began to read just how important the cotton industry was, and had been, not only in Burnley, but all over the world. It was not the fashion industry which interested me. My twice weekly “dose of fashion”, through the pages of my daily newspaper, the Independent, I still regard as an unnecessary intrusion into my reading. You can observe how little influence newspaper articles on fashion have had on me by merely opening the doors of my wardrobe!

Many of you will remember the late Tony Wilson’s proposal for a Fashion Tower in Burnley’s Weavers’ Triangle. I realise he had been consulted about ways to make this part of town as vital to Burnley as it once had been. But, Burnley’s cotton industry was not about fashion. It never had been. It was about cloth. There is a difference.

I was reminded about this at a recent television screening of the film “The Man in the White Suit” starring Alec Guinness and Cecil Parker. It was filmed in Burnley in 1951 and the textile firm in the story was “Birnley’s” – notice the subtle substitution of the “u” for an “i”! The pronunciation, of course, did not change except the actors had clearly not visited the town and “Burnley”, when they said the name of the town, sounded rather different on their lips when compared how I hear it at Turf Moor.

Important as the cotton industry was to Burnley, it was even more important to the country. One way of demonstrating this is to consider Britain’s trade figures. I happen to have the figures for 1923 to hand and they reveal just how important cotton was to our national economy. It should be added that 1923 was, perhaps seven or eight years after the peak which had been reached just after the beginning of the First World War for most of Britain’s traditional industries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1923 the total value of the merchandise imported into Great Britain was c£1.1b with exports worth £886m. Notice there was a “trade gap” even then. The principal imports were grain and flour, £96.9m.; meat £125.7m.; other food and drink, £116m.; raw cotton £93.5m.; wool, £50.3m. and metals, machinery and ores, £55m. The largest exports were cotton goods, £179.3m; woollens, £64m; chemicals £27m.; machinery, £46m. and metals and manufactures, £102.6m.

These figures show a number of things about cotton. The first is that cotton was, by far, the largest of the export industries and added value to the raw cotton as imported, by a factor of two.

Of course, these figures do not include the value of the cotton retained in Britain. Raw cotton imports were 11.6% of total imports but cotton exports were just over 20% of the total. Another way of looking at the situation is that out of the total raw cotton imports some 85%, or thereabouts, was re-exported.

One fifth of all of Britain’s exports were of cotton and cotton goods and it is likely a large percentage of the machinery exported was in textile machines and other equipment for textile mills. A commentator at the time noted that: “In the cotton industry Great Britain still remains a long way ahead of other countries.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnother important fact, taken from the 1923 figures, is that 577,000 people worked in the British cotton industry in that year. This was down on the 620,000 employed in the industry in 1912 but, taken with the other textile sectors, it was the third largest of the employment categories after engineering, which included ship-building and all the metal trades, the largest, and mining, the second largest.

Locally, Burnley was the leading centre of cotton weaving with, in 1933, 101,000 looms. Blackburn came second with 93,000 looms and Preston third with 68,000 looms. Of course all three towns had spindles but, in this respect, both Blackburn and Preston were larger than Burnley though nowhere near as big as Oldham with 17.4m spindles.

It is worth pointing out these figures relate to a time when the industry was already in decline. The loomage of both Burnley and Blackburn had been considerably larger at the time of the First World War.

In the series, I will be going into some of the issues which I have raised so far and I will also be assessing Burnley’s contribution to the development of the Lancashire Loom, a subject which rarely mentioned in publications on the subject.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMuch space is given to Edmund Cartwright, the inventor of the power loom, and to Blackburn, where important improvements to his loom were made, but Burnley’s inventors have been marginalised, something with needs to be put right.

The story of the introduction of cotton into Burnley is also, as I hope you will discover, an interesting one. It exists in a number of different sources but no one, to my knowledge, has put it together in a systematic way. This is the intention of this series but it should be noted that I will not only be talking about the weaving of cotton. It must be remembered Burnley was a centre of woollen production long before it became a cotton town and factory-based cotton spinning was introduced before it happened in weaving.

We start in earnest next month by reminding ourselves about some basic details about textiles, and particularly the cotton industry, as they apply to the Burnley area.

I feel this is necessary as many of you, as I indicate above, will not have this information.

Hopefully, it will helpful in your understanding of the series.