Recreating Burnley of the 1820s

A decade later, the Emeritus Professor of History at Manchester, T.S. Willan, produced a book “Elizabethan Manchester”, published by the Chetham Society. Remembering my boast, I bought a copy and, though the professor had studied the subject in much more detail than I had managed, he, using very much the same sort of evidence as I had done, came to very much the same conclusions.

Back in 1968 I even took the group on a conducted tour of Elizabethan Manchester. I know you will not believe me but it did not degenerate into the usual student booze up! It was, in fact, a fairly easy exercise because, once aware of a number of basic facts, other information falls into place. Key to the relative success of the tour – the first of many tours I have organised – is the size of Manchester in Elizabethan times. Daniel Defoe, writing of Manchester in the early 18th Century, called it the “biggest mere village in England”. At the time of Elizabeth (1558-1603) it was much smaller.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnother important point to remember is that, surprising as it might seem, a number of buildings in central Manchester would have been familiar to Elizabethan Mancunians. I refer to the Cathedral, Chetham’s School and Sinclair’s, the first two of which had different origins.

The early history of the church in Manchester is obscure but it is thought there was a church in the old part of Manchester in the 8th Century. There was another church, possibly on what is now St Anne’s Square, by the 10th Century but the church mentioned in the Domesday Book (1086) is not this one but another place of worship located close to St Mary’s Gate. This building was founded by King Edward the Elder, son of Alfred the Great, in the early 10th Century.

The building now the cathedral, formerly Manchester Parish Church, was not founded until the early 13th Century, possibly in 1215, the same year as Magna Carta. The site chosen was in the close of the Manor House which survives as Chetham’s School. In fact the church, which became collegiate in the early 15th Century, and the Manor House were, for over a century, inextricably linked in that the canons (priests) who served the church made the building their place of residence.

Thus, in the unlikely heart of industrial Manchester, England’s only surviving medieval monastic foundation, which remains complete, can be found. With information like this it is not difficult to recreate what this part of Elizabethan Manchester looked like. In these examples the buildings survive and this is the case with Sinclair’s, now a famous Manchester eating establishment. This building is of half timber construction and its survival indicates what other buildings in what is now the city would have looked like over 400 years ago.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn addition, another factor helps us to recreate what Manchester would have looked like at the time of Elizabeth. Very helpfully, until recently, the medieval street pattern survived in Manchester. St Mary’s Gate and Deansgate are only two of these. There is not the room to mention others but, even though the City Council has allowed the construction of some dreadful buildings in the historic centre, there still remain a number of streets that follow, in part mostly, the ancient routes of earlier times.

Another aid to recreating what Manchester looked like is the landscape itself. It should, in this instance, be the “cityscape” but enough of the natural shape of the land upon which Manchester was built survives for it to be helpful to us. All school boys know how Manchester got its name. The name was initially given to a small fort established by the Romans at what is now Castlefields, near the present day Manchester Museum of Science & Industry. The fort is believed to have been built by Agricola in AD79 when he was leading the Twentieth Legion in its conquest of much of Britain but the soldiers noticed the two small hills in the area, the one became the site of the fort, the other, at a later date, the site of the Manor House and later still, the Collegiate Church. They, therefore, called the place Mamcestre and, if you know your Latin you will know why!

The point is that the area around the cathedral, although it has changed dramatically, still retains some of the character of the original virgin site. The slight hill upon which the cathedral stands, the route taken by the Irwell and the Irt together with a number of building lines give someone who can interpret these things an insight into what the place looked like years ago.

There are two examples of what I mean. Those who have written about the city of Manchester in recent times often refer to the location of the cathedral in less than complimentary terms. They compare Manchester with Durham and Lincoln saying Manchester Cathedral is of little consequence when compared to these great ecclesiastical buildings. They forget, however, that the cathedral in Manchester was built as a mere parish church but that, when it served that purpose, it totally dominated the place it served. It was, by far, the biggest building in Manchester and atop its small hill it could be seen for miles around. The Collegiate Church was a great landmark until the industrial era.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe final point in the recreation of Elizabethan Manchester is that we are helped by place names. I will only give you two examples but once you realise what they mean you will see how they might help in the task in which we are engaged. The place names are Stretford and Trafford. These fords gave Agricola’s Legion access to Manchester, the natural place at which to build his fort. The ford at Stretford made it possible to get across the Mersey; that at Trafford to get across the Irwell.

Both rivers were important waterways in the past, used for transport. In fact the Irwell, difficult to believe these days, was once full of fish and was the site of the northern equivalent of the Oxford & Cambridge Boat Race. This latter continued into the 19th Century and there is even an account of a man with Burnley connections drowning at such an event!

The place name Stretford means the “ford where the Roman road (strete) crossed a river”. The first part of the name comes from the Latin from which the Italian “strada” comes, as in autostrada (motorway). Trafford means literally “a ford in a valley” so it has not got Roman connections but both of these fords determined, to some extent, the routes people had to take to get into Manchester. Once you know this much else falls into place.

I have written about Manchester rather more than I might have done but hope what I have said will be a prelude to a few studies I have made along the same lines in the Burnley area. It is not generally realised that the ancient street pattern in Padiham, for instance, is still intact. How many of you Padihamers realise that when you walk down Mill Street you are using one of the older routes in the area?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn recent times I have described what the old route to Briercliffe was like and one of the themes of “Peek into the Past” in 2014 is going to be to follow other roads in the borough to see what they were like in the days of our ancestors. I am also going to try to recreate what parts of Burnley were like in different periods in their history.

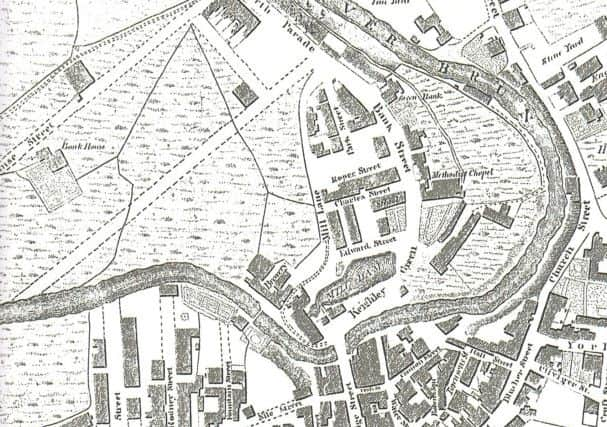

Today, I am going to conclude by taking you to see the Church Street, Yorkshire Street and Gunsmith Lane area as it was in the 1820s. This is not as difficult as you might think as the Burnley & District Historical Society has recently reproduced copies of Fishwick’s Map of Burnley of 1827. They are now available at Burnley Local History Library at £5 each and this edition is the best and most detailed I have seen.

In 1827 the Leeds & Liverpool Canal had been completed but the railway had not yet come to the town. The canal was a great barrier to the development of the town to the south and east but Burnley appears to have been prospering. New and intended streets are marked on the map in the Bankhouse area and it is clear Pickup Croft, the location of the present bus station, the library and former Thompson Centre, are also ready for development.

I started a description of the St James’s Street area, which was published some time ago, at the Yorkshire Hotel which stood at the junction of Gunsmith Lane and Yorkshire Street. This short tour will begin at the same location. In 1827, the Yorkshire Hotel was a private house with large gardens to the rear. We know what these looked like because of the observations of a writer who mentions them in his memoirs. Briefly, there were flower gardens, orchards and vegetable plots – all in the centre of Burnley!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey were not alone as there were attractive gardens on the site of the present Keirby and others in Church Street, at Hill Top and by the Regency period Scars House and Adlington House, now the Coach and Horses. Of course, there were stone yards, timber yards, a tan yard and the sites of early mills in the Church Street area.

Opposite the Old Sparrow Hawk there was the New Sparrow Hawk which had its own extensive gardens.

Just below the Old Sparrow Hawk, the houses in Church Street also had sizeable gardens and, beyond St Peter’s Church, perhaps the largest of the “town centre” private gardens, was located. This was part of the property belonging to Brownhill, a large house belonging to the Holgate family of bankers, which had been completed only a few years before.

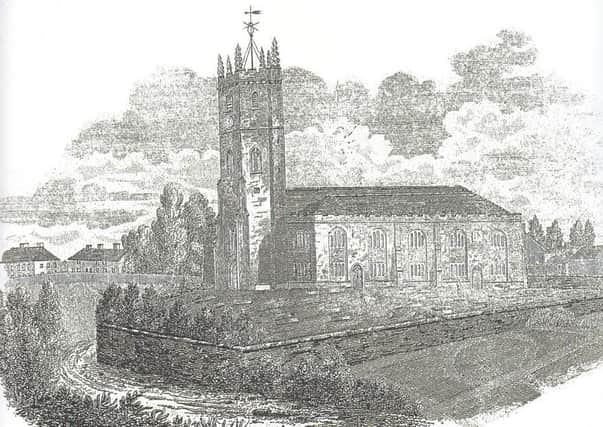

A drawing of St Peter’s Church is appended to the map. It shows the building before the extensions of the mid 1850s which were carried out by the firm of Austin & Paley of Lancaster but after the changes to the building which were undertaken in the 1790s and early 1800s.

This drawing just gives you a hint of what pre-industrial Burnley looked like. It is a hint upon which we will expand in coming weeks.