Exploring the Anglo-Saxon history of Padiham

To some extent, with regard to Padiham, the lack of a written history has been addressed by a number of local writers and Padiham Archive Group. There are walkers’ guides, or trails, to Padiham and there is a written history of the former Padiham Unban District Council together with studies of individual streets but no attempt has been made to draw existing work, which is more extensive than has been listed here, with new work on subjects that have not, in the past, been given the treatment they deserve.

In comparison with Padiham, Hapton and Higham have little written history, though it can be found if a search is instigated. The children of Higham, in recent years, produced a lovely guide to their village and a recent award of Lottery funding has resulted in considerable historical work in Hapton.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPadiham is first recorded as Paddingham in 1251 but the name is Anglo-Saxon in origin. It was known as Padingham in 1294, the same year Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, obtained the right to hold a market in Burnley. In later years Burnley’s Market Charter was the cause of rivalry between the two places as it forbade the operation of other markets within six miles of Burnley market. Padiham falls within the six miles but this did not stop the town demanding its own market in the early 19th Century.

It seems Padiham first saw the light of day as a small settlement as early as Anglo-Saxon times and it is supposed the name derives from one Padda, perhaps a local leader or chieftain. Of course, this is supposition but the antiquity of the place is confirmed by the existence of part of the medieval street system which can be identified in the upper part of town.

Along with most other places in North-East Lancashire, Padiham is not mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 though it is likely there was a settlement there. This has been explained by the understanding this part of what later became Lancashire had been devastated by William I in the early 1070s after a rebellion against him in the north of England.

Another possibility is the part of the country, extending from the Mersey in the south to Carlisle in the north, was particularly backward, cut off from the rest of the country. In 1086 there was no County of Lancashire. When the Domesday Book came to be compiled the northern part of the later county was included with Yorkshire and the southern part in Cheshire. There were no sizeable centres of population in this part of the world and similarly there was no main road, cathedral or significant monastic institution. It is possible those charged by the king to compile the book did not feel they could operate safely in the area which became Lancashire and, consequently, spent as little time as they could here.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPadiham had an ancient corn mill, its church was established in the 15th Century and the small town had a share of the woollen and linen industries. However, like many places in Lancashire, it did not see significant growth until the coming of the cotton industry. At the town’s peak, in the years before the First World War, it had 21 cotton mills a number of which were very large but coal and engineering were also important employers.

In terms of transport, Padiham was served by several turnpikes, but it had no canal and rail came to the town a number of years after several lines had been built in Burnley. Padiham had a station on the Great Harwood Loop line which was completed in 1877 though it was one of the lines closed before the Beeching cuts of the 1960s. The Great Harwood line, which provided an alternative rail route between Blackburn and Burnley, was closed in 1957.

However, part of the line was in use to carry coal from near Rosegrove, Burnley, to the large Padiham Power Station which was built, almost 60 years ago on the site of one of Padiham Unban District Council’s great achievements, the towns own electricity generating station.

Padiham has a number of “claims to fame”. Those associated with the Kay-Shuttleworth family have been noted in previous articles but it is not generally realised the leisure-time pursuit of competititive hill walking owes much to the activities of Padiham men who, often for money, would hold races on Padiham Heights, a beautiful, wooded, hill top area between Padiham and Sabden.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the 19th Century the Burnley area had three horse racing tracks. The most well known gave its name to Burnley Football Clubs modern ground, Turf Moor. There was another track in the southern part of Burnley, formerly Habergham Eaves, not far from the modern Rosehill but the third track was in Padiham, to the south west of the Calder and it survived until the 1860s.

Brief as this is, Padiham has a fascinating local history. At the present time it is visual rather than written and some have claimed it is not unlike the British Constitution, unwritten but there all the same. The excellence of the visual nature of Padiham’s history is the consequence of the work of Padiham Archive Group which operates from rooms in Padiham Town Hall. They have gone a long way to help preserve Padiham’s past though the narrative history still needs to be addressed.

If we look now at Hapton, we know there was a settlement of some kind there as early as 1241 when it appears to have been known as Upton. In 1243 the place was known as Apton which is recorded as Hapton in 1246 and again in 1280. The place name is descriptive of the area which it occupies, a hill occupied by tun, an enclosed piece of land. It is from the word “tun” we get our modern word “town” though this does not mean the early Hapton had the status of a town. It is more likely it was an enclosed area protected by a fence or a ditch, perhaps both.

This latter is significant as, in the late 15th Century, Hapton was enclosed by the Lord of the Manor, Sir John Towneley, and converted into the second largest hunting park in Lancashire. In doing so, Sir John, who also achieved much in his lifetime, made himself, to Haptonians at least, the most reviled of men. The reason for this was that he deprived a number of people of their settlements, legal or otherwise, consigning, it is thought, at least some of them to beggary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHapton is unlike most of the places in this area as it once had a castle. Little is known about it though the site is known and it was once considered for an archaeological dig. Unfortunately, the dig did not come off as local landowners objected. However, it is understood the castle may have been an illegal building constructed in the lawless years of the reign of King Stephen who was on the throne from 1135 to 1154 when Henry II came to the throne. Henry, and subsequent monarchs, banned illegal castles many of which were destroyed or abandoned.

The place also has Hapton Tower, once the preferred home of the Towneleys of Towneley. This building survives in a ruinous condition on the lower reaches of Hameldon. It is difficult to believe, on visiting the site, barren and windswept, anyone would prefer this location to Towneley but the views from the site are well worth the climb and the building was at the centre of the Towneley hunting operations at a time when the Royal Forests were disforested in the early 16th Century.

Hapton also contains the sites of two deserted villages, “Birtwisle” and Shuttleworth. It is supposed they both were terminated by Sir John over 500 years ago. The former was in the Hameldon area and all of those who have the surname Birtwistle, including our current MP, take their name from this place which was in the Old Barn area of the parish. Shuttleworth Hall, which is dated 1639, still stands in the lower part of the parish but it is not known for certain where the village might have been.

In more recent years Hapton has had an interesting industrial history which has included coal mines, cotton mills, calico printing works and chemical factories as well as a small electrical engineering works which made Hapton famous as the first village in England to be lit by electricity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, Hapton has long since been overshadowed by Padiham and it is sometimes difficult to extricate Hapton’s history from that of Padiham.

Higham’s is a different story and, again, it has a fascinating history. The proper name of the place is Higham-with-West Close Booth and the former is first mentioned as Hegham in 1296. This name means the “high ham” or “high home”, a settlement on a high hill, a perfect name for this lovely village. West Close Booth is first mentioned as late as 1323 but the name derives from the Old English and means “the western dairy farm”. The area is sited on lower land between Higham and Ightenhill.

Both Higham and West Close have interesting histories. Higham became the site of the Manorial Courts which had met at the Manor House at Ightenhill until 1525. West Close Booth was intimately associated with the Lancashire Witch story as one of the two main families lived there.

The whole of Higham, including West Close, was within the Royal Forest of Pendle until disforestation took place in 1507. There had been three royal or ducal vaccaries, cattle farms, in the area before 1507; one at West Close and Hunterholme, another at Higham Booth (the site of the present village) and the third at Nether Higham, the part of Higham in the Sabden valley.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn more recent times Higham had coal mines, cotton mills and a well-known shuttle works. The village even had its own Co-operative stores, something present day residents find difficult to believe. However, if you know anything about the history of Higham, it does not concern the lives of wealthy families because, until recently, there were few in Higham.

Higham’s story is of agricultural labourers, handloom weavers, miners and shuttle makers and this can be seen to this day in the name of the very much haunted village pub, “The Four Alls”. The inn sign depicts a king, who rules all; a soldier, who fights for all; a cleryman, who prays for all and a poor man who, crippled with taxes, pays for all!

It was the inn that was the centre of village life when, in the early, 19th Century, William Varley of Higham wrote his famous diary. He also left to us an account book which is very useful when describing the life of a poor handloom weaver.

There are a number of “monuments” in Higham – the beautifully preserved pinfold, the spring which was the source of village water, the residential street named after Sir Jonas Moore, the 17th Century engineer and mathematician and builder of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich – but there is no memorial to the Lancashire Witches some, of whom knew Higham better than they knew Newchurch-in-Pendle, and there no memorial to William Varley, whose life epitomised that of the common man in the years immediately after the Napoleonic Wars.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

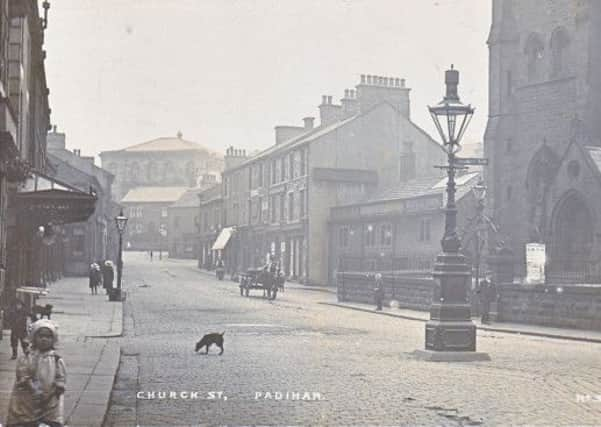

Hide AdThe pictures which accompany this article have been chosen in very much the same way as the pictures published of Briercliffe, Cliviger and Worsthorne a few weeks ago. I hope those of you who live in Padiham, Hapton and Higham enjoy this piece of work as much as I have been told your neighbours enjoyed the first.