‘Cotton Town’ grew from a centuries’ old industry

The word “former” is important because Burnley, with only one “production unit” at the present time, can no longer be regarded as a “cotton town”. Cotton, so far as Burnley is concerned, is virtually confined to history; in effect to Queen Street Mill Textile Museum, Harle Syke, now given a degree of protection on a par with Towneley Hall and St Peter’s, our magnificent parish church.

We are very fortunate Queen Street Mill, and its contents, have survived. Many towns which were once associated with great industries have little or nothing left for their citizens to see and experience, but Burnley has the world’s last surviving steam-powered cotton mill and much of the Burnley-made machinery installed in the mill when it opened for business in 1894.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis G herbaccum series will examine Queen Street Mill Museum in future articles but the story on which we are about to embark does not start in Briercliffe. It starts with the genus Gossypium of the natural order Malvaceae. In England this family of plants is represented by the hollyhock and hibiscus of our gardens, and the wild mallow with its pale magenta flowers and downy foliage. Its seeds have a mild flavour and may be eaten harmlessly, but they do not produce the fibres called cotton like their near kinsman the gossypii.

The mallows, which are so endowed, are natives of the Near and Far East and also the Americas. They are cultivated in the Old and New World, 30 degrees north and south of the equator. The North American “cotton plant” has two varieties – Gossypium barbadense and G hirsutum - which produce fine, soft, silky, long staple fibres of about two inches in length and a short staple with a fibre of about half that.

The long staple cottons are the best and the very best of them are known as Sea Island Cottons and were grown in the southern states of the United States, but especially on the islands bordering the Atlantic coast. The cottons of South America and Egypt were mostly obtained from G brasilience (also known as “kidney cotton”) and the Indian cottons are derived from G herbaccum which produces another short staple fibre.

There is a plant which is native to Britain which is known as “cotton grass”, the popular name of the plants of the genus Eriopharum, order Cyperaceae, or sedges. There are several species of these plants which grow in boggy, moory places. They produce a cotton-like substance which used to be used for stuffing pillows, though I think this has ceased. Cotton grass is not related to the cotton which came to be used in the Lancashire textile industry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe history of the plant we know as cotton starts in ancient times. The first references to it are in India and its adjacent islands centuries before the coming of the Christian era. It was known in Egypt by the 6th Century BC and was introduced into Europe by the 9th Century AD by the Moors of North Africa who planted the cotton shrub in Valencia, Spain. They also established factories in Granada and Cordoba and it is from the Moors the word cotton is derived.

The Moors were followers of Islam. Their language was Arabic and the words from which “cotton” comes are “qutun” or “kutun”. However, the French used a derivative word “coton” and it is this gives us “cotton”.

Italy had learned how to use cotton by the 13th Century and that knowledge gradually spread from there to the Hansa towns of the European Plain, and especially to the textile towns of the Netherlands. It was from here that cotton reached Britain in the 14th Century but, from the 16th Century, a large number of Protestant refugees from Holland (Flemings) were welcomed into England. They brought with them the advanced knowledge of how to work cotton, though, at this time, its usefulness was considerably less than both wool, derived from sheep which were common throughout England, and linen, derived, like cotton, from another vegetable, namely flax. The latter, as we shall see, was grown extensively in Lancashire in the 17th and 18h Centuries.

Cotton was also known in China at a very early date but it was not manufactured there until the 14th Century.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

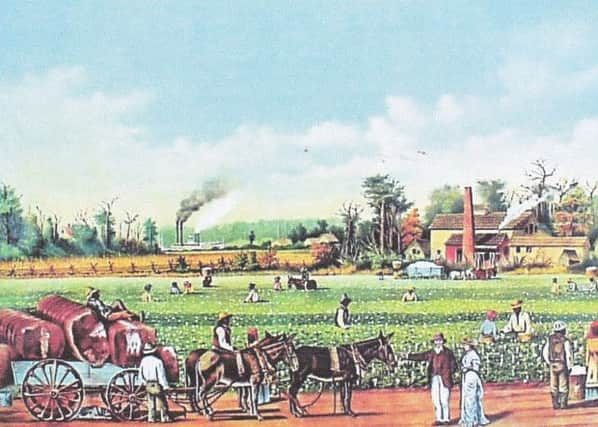

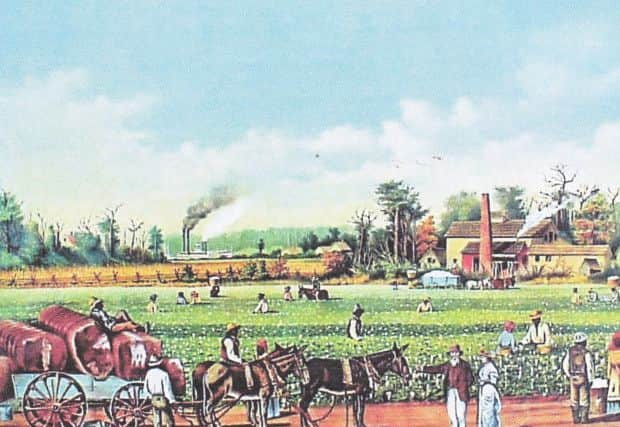

Hide AdThe next great step in the advancement of cotton took place in 17th Century Virginia in what was to become the United States of America. In 1621 cotton was planted by English colonists but it took some time before Virginia could produce enough for export. As late as 1780 to 1790 Britain obtained most of its raw cotton from the British West Indies, which also supplied Britain with sugar. From 1790, the former colonies, now the United States of America, started to export cotton in large quantities to Europe, but mainly to Britain. So far as the export of cotton is concerned, the USA soon out-distanced everyone else.

In time Britain would come to dominate the world in the production of spun and woven cotton goods but it was not an easy transition. Just before the United States of America was founded, after the American War of Independence (1776-83), Britain had won a stunning victory against France in the Seven Year War (1756-63). This war had been fought in Europe, India and North America and, in many respects, constituted the first of the world wars.

Its importance to us is that Robert Clive’s victories in India ensured the subcontinent would become a British possession. The extension of British rule in India, at first through the East India Company, brought Indian cotton goods to the attention of the British market. Such names as calico (from Calicut, or Calcutta as it became better known to the British) and muslin (from Mosul), both cotton fabrics, are reminders of these days.

The natives of India, by the exercise of great patience and by skill acquired through long practice, made cotton goods of great excellence and beauty. English cottons were, at best, pale imitations of Indian goods, most cotton here being used in the production a material called fustian, about which there will be more in a future article. Briefly, fustian was a material made by the combination of a woollen warp and a cotton or linen weft. In other words when cotton was used, the resultant material was only half cotton and could not be compared with Indian calicoes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOf course, Britain already had its own textile industries, wool and linen and, to a lesser extent, silk. The first of these was the ancient staple and there were important woollen areas in the West Country, East Anglia and the West Riding of Yorkshire. However, the production and “manufacture” of wool was a national industry and East Lancashire – Colne, Blackburn and Burnley – had a part in the woollen industry.

We also know Blackburn and Burnley were involved in the use of flax in the production of yarns and cloths derived from that plant. Later in the series we will look at the wool and linen industries in our area. They both pre-dated the cotton industry and the producers of wool, in particular, realised the new Indian cottons were a real risk to their trade. By the use of legislation they protected their own industry to the detriment of the new cotton industries whether they were British or Indian.

Cottons had a number of advantages over wool. It was easier to wash and dry cotton which also took dyes much better than wool. It was also easier to print cotton than wool and the now much-derided chintz, a printed all-cotton fabric which was produced in India, became very fashionable in Britain mainly for upholstery. Incidentally, the word “chintz” comes from the Hindi word “chint” which derives from the Sanskrit.

There was, in the England of the 18th Century, a huge change in fashion which favoured a move from the relatively dull and heavy British fabrics to the colourful and light Indian ones. At first, such was the demand that Indian fabrics sold at very high prices in Britain. They could only be bought by the very rich and soon the race was on to produce all-cotton British made textiles from cottons mainly imported from North America.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first consignment of raw cotton from the United States was imported by the firm of William Rathbone and Sons of Liverpool in the 1780s. The cotton arrived in eight bales and three barrels and caused Mr Rathbone some difficulty as the Customs Office in Liverpool was of the opinion its importation broke the law. It was 18 moths before the consignment could be sold.

Little could Mr Rathbone have known but this small difficulty would soon be forgotten. Within a very short space of time Britain was devouring great quantities of American cotton and not only were the British people demanding all-cotton fabrics, made mainly in Lancashire and its surrounding counties, but events were to conspire to make the rest of the world demand exactly the same.

Of course, the story does not stop there. We have barely mentioned Burnley yet. In fact, as we shall see, Burnley was a late-comer to the cotton textile industry though that did not prevent its greatness as a centre of cotton production and textile engineering.

Next month we will undertake a second article looking at some of the terms relating to the cotton industry, the study of which is impossible without understanding them.