How our history contributed to flooding nightmare

I could mention other examples of flooding in our immediate area but, to my knowledge, these are the worst that have had to be endured this time. I say “this time” as the Burnley area has quite a history of flooding. It might not, in our town, match the problems of the Somerset Levels, York, parts of the Lake District, or even Whalley, Ribchester and Croston, but there have been some spectacular floods in our part of the world over the years.

I will tell you about some of them in a future article but, today, I want to address the reasons why floods have occurred. First, let me say, to those of you who have been affected, particularly in Padiham, the rest of us hope your problems will be over as soon as possible.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis article had had to be rewritten to some extent. In my first draft I mentioned that the local council, Environment Agency and other interested parties do not appear to have got their respective acts together since the flood emergency. Now, some two weeks after the flooding incidents, there have been a series of announcements acknowledging the problem though none of them approach the urgency required. I will be looking for more from our MP, for instance, than calling on someone else to do something.

It is not normal for a town, in a situation like that of Burnley, to be affected by flooding as often as historically it has been. Flooding usually takes place lower down the course of a river system than the case here. York, Tewkesbury, Worcester, Carlisle, Selby and Goole are good examples of these but here, in North-east Lancashire, one of the main factors is the volume of rain which falls in a relatively small area.

Water catchment in our part of the area is very complicated. Most of the water comes from the north, east and south east of Burnley. There is some from the south and west but south of Burnley the hills rise quickly to Rossendale and most of the rainfall makes its way, over the watershed, to the Irwell. To the west the rivers and streams, generally, flow in that direction and do not trouble Burnley.

However, there are three main river systems, or catchments, which converge on Burnley. It would be more correct to say they converge on Padiham as that town has to deal with the waters of all three catchments. Burnley has to deal with only two of them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first, and most important of the rivers which flow in the direction of Burnley and Padiham is Pendle Water. In Higherford, which is on its course, the river is erroneously referred to as the Calder. There are cottages in Higherford known as Calder View but the river is Pendle Water. This confusion was apparent over 200 years ago when William Yates published his map of Lancashire. He names the river at Holme End, at the bottom of Barden Lane, as the Calder, but gives no name for the river to the south-east of Burnley which, confusingly, begins its journey above Holme-in-Cliviger and which is now known as the Calder. To be even more precise, this latter river is the Lancashire Calder.

Why is it that Pendle Water is the most important of our rivers? If we look at its drainage area it can be seen the waters of the river come from two of the places with the highest rainfall in the district, the area around Pendle Hill and the area near Wycoller. On the steep south side of Pendle Hill, the head waters of Pendle Water appear as Ogden Clough. At the village of Barley, another stream joins it to become Pendle Water near Roughlee. It is here, to the south-east of Pendle Hill, that the greatest amount of rain falls. In fact, the situation of Pendle makes the whole of the district, to its south and east, much wetter than the areas to the north and west.

The second of the sources of water, in the Pendle Water system, is Colne Water which forms from the river Laneshaw and the Wycoller Beck. They eventually join Pendle Water near the aptly named Reedyford, near Nelson. Not far from here Walverden Water, flowing north-west from Briercliffe, also joins the river. Much enlarged, given the distance involved, Pendle Water makes its way through Carr Hall, and Victoria Park, both, as we have seen, very wet areas. In fact “Carr” means, literally “wet, or boggy land”. The river then passes on to Lomeshaye, also the site of many floods in the past, and through to Brierfield, from where Lower Reedley and Pendle Bridge (at the bottom of Barden Lane) are reached. Pendle Water ends its journey at Royle, to the north of Burnley where it disgorges itself into the Lancashire Calder.

The next river system is that of the Brun, which rises to the north-east of Burnley and is formed out of a confluence of Hurstwood Brook and Cant Clough Beck, near the village of Hurstwood, though there are other small streams involved. The Brun is also joined, near Heasandford, by the River Don (the shortest river in England) and its head waters, the Walshaw Clough, Cockden Beck and Thursden Brook. Swinden Water wades in also at Heasandford. Then the Brun joins the Calder at the Water Meetings almost in the centre of Burnley.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe last of the systems is that of the Lancashire Calder. I have been using this name to distinguish it from the river of the same name which flows through Todmorden and Hebden Bridge eventually to join the Humber. Our Calder, rises in the eastern part of Cliviger. There are no main confluences with sizeable streams but the Calder is joined by lots of tiny ones before it gets to the former Towneley Estate where the river has flooded regularly in the past. There are other places, between here and the Stoneyholme and Royle areas, where the Calder has historically flooded. They are too numerous to name individually though the areas have not flooded in modern times because of changes to the course of the river.

On the north side of the present site of the College, though it is some distance away, the Calder gets to Royle where the big confluence, known originally as the Water Meetings, takes place with Pendle Water. The land around here was particularly wet in the past and a number of local names, used even today, remind us of this. Stoneyholme, means the “stoney island” and Salford, nearer the town centre, means “the ford where the willows grow”. Willows require wet land to prosper and there are still plenty of specimens of this small tree on the much altered banks of this part of the Calder.

Of course, the now vigorous Calder, containing the waters of three systems, still has to make its way to Padiham but, as it does so, it passes through a number of areas which once, acting as flood plains, slowed down the river. The largest of these sites is now occupied by much of Padiham town centre and that is why this area floods so frequently.

So the high rainfall, in a relatively small area of the Lancashire Pennines, is one of the reasons for the flooding that takes place here. Another is that the “flood plains” in Waterside (Colne), Carr Hall (Nelson), Burnley and Padiham are being used in ways that are not in the best interests of the community.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn Burnley a number of problems exist, some of them man made. The first of these is that both the Brun and the Calder have been confined to narrow channels. In the past the Brun overflowed, almost annually, in the Wapping area of the town centre. Some of the buildings were marked and dated showing how high floods had been in the past. Though these buildings are long gone, there is still a place, on the Brun, which retains similar markings. They can be seen at the Sandholme Aqueduct above Thompson Park.

The situation on the Calder, as it flows through Burnley, is the more problematic. The existing flood plain at Lower Towneley still does its job of delaying the passage of excess water as it flows from Cliviger to Burnley. Beyond that, before the former fields were built over, there was regular flooding in Burnley Wood, Fulledge, Lane Bridge, Bridge End and at the confluence of the Brun and the Calder.

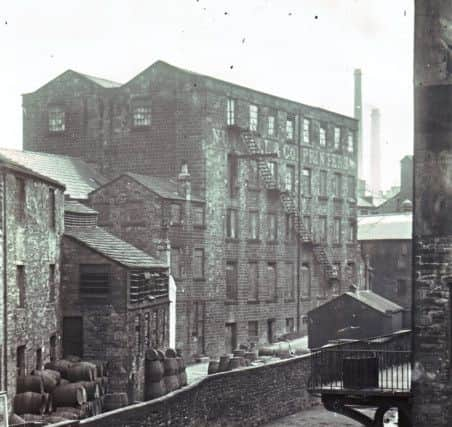

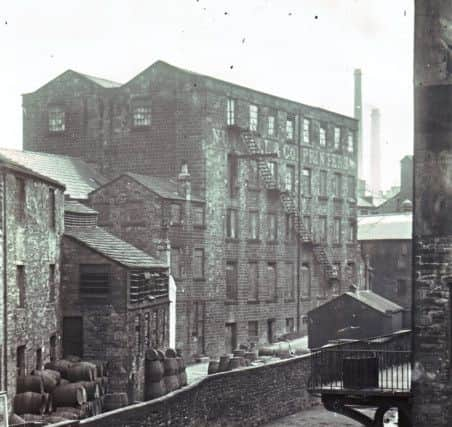

The confining of both the Brun and the Calder into narrow courses speeds up their flow rather than the opposite, giving the river the potential to do more damage downstream. Some people think the Calder, for example, was put in its channel so that, in the 19th Century, the town could get rid of its sewerage more quickly. This is not the case. The intention was to speed up the flow of water so it cleared Burnley allowing factories and houses to be built.

Though, in recent years, the flow of water through this system has been slowed a little, the overall effect has been to increase the speed of the flow of water into Padiham where, without the appropriate defences, the Padiham flood plain fulfils its historic task.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is worth having a look at the Padiham site in a little more detail. Historically, Padiham was located on the high land to the north-west. It is there that you will find the oldest streets – Church Street and Mill Street – and, on the same hill, is the Parish Church and some of the town’s oldest buildings are located there. These are all constructed on this land as the property nearest the river was wetter and liable to flooding.

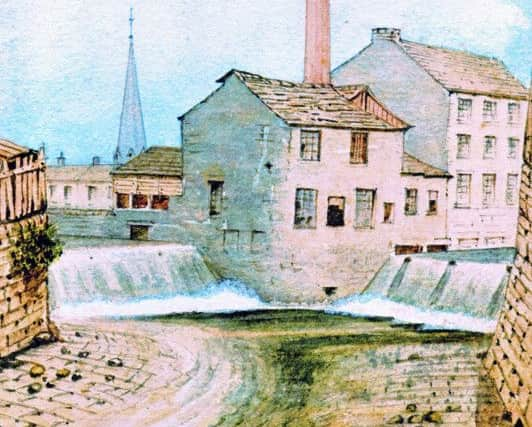

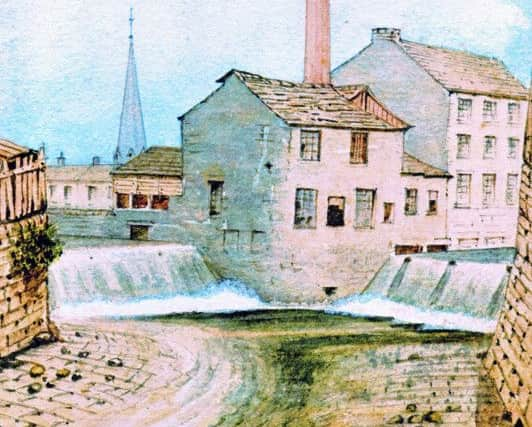

Of course, Padiham’s low lying land still had its uses. It could be used for grazing and that is how what is now Padiham Town Centre was used, ie as water meadows. However, when the town was industrialised, beginning in the later 18th Century, the low lying land was the first to be developed as it was the cheapest on which to build. Soon, houses and shops were built and the problem which now exists in Padiham was created.

It is not too late to do something about the situation in Padiham and there are several ways of doing it. The first is to prevent excess water from overflowing in the town centre. A number of measures are available, including the building of barriers, but schemes of this kind are often expensive. Another, potential solution is to slow down excess water higher up in the catchment areas. This can be done by planting trees, extending mossy areas and building simple mechanisms which slow down and retain water.

The 1.2 million trees planted in the Forest of Burnley Project will have helped and the recent work, carried out by the Ribble Rivers Trust, in slowing down the flow of water, especially in the Calder in Burnley and above Burnley, will have had an effect except in the most extreme of circumstances. Also, a suggestion published, in our local newspaper, that some form of dredging be implemented at strategic locations should be looked into.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere is, though, plenty more that can be done. United Utilities needs to plant more trees in their water catchment areas. Farmers need to reduce, even further, the number of sheep that they have on the moors above Burnley and in the area near Pendle Hill.