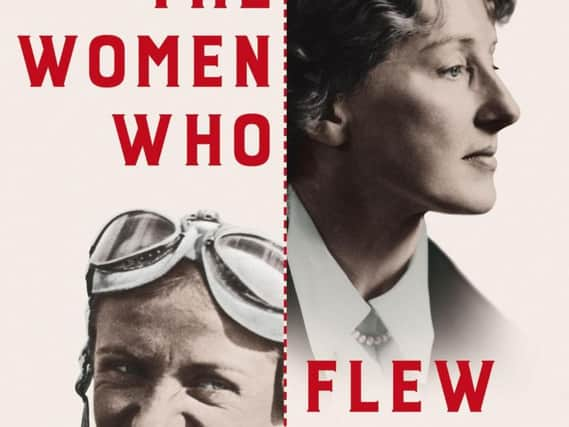

Book review: The Women Who Flew for Hitler by Clare Mulley

Hanna Reitsch, a feisty blonde with blue eyes and a winning smile, and Melitta von Stauffenberg, a scholarly, aloof aristocratic woman who was also a brilliant engineer, became two of the Führer’s most prized test pilots, taking to the skies on death-defying, pioneering flight missions.

Their extraordinary and little-known stories – like the two women themselves – were wildly different. Whilst both made military history with their daring exploits in a Nazi regime that was inherently prejudiced against women, their rivalry was notoriously bitter and they ended their lives on opposite sides of history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdClare Mulley, award-winning author of three biographies, has produced a stunning dual exploration of these two remarkable flying aces, retrieving their chequered, interwoven lives from the dusty corners of history, reassessing their wartime careers and providing fascinating insights into Nazi Germany and its attitudes to women, class and race.

Hanna and Melitta, two talented, courageous and strikingly attractive women, fought convention to make their names in the male-dominated field of flight in 1930s Germany. Middle-class, vivacious Hanna, with her distinctive Aryan looks and go-getting energy, was a champion glider in the years between the wars, making her name as a celebrity-seeking, over-confident daredevil.

Hanna was also a fanatical supporter of the Nazis and the Führer, a rabid anti-Semite and remained a Holocaust denier right up to the end of her life. She was feted by Hitler’s henchmen and she was awarded the Iron Cross in recognition of her achievements.

When the tide of the war finally turned against Germany, Hanna went to join Hitler in his bunker in Berlin and begged him to let her fly him to safety. He turned her down so she offered to die alongside him but again he refused and she was ordered to leave with one of the generals.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMelitta, who was also awarded the Iron Cross, was more than just a test pilot; when she wasn’t in the cockpit of a Stuka dive bomber, she was at her drawing board, working on the development of planes in her high-level job as an aeronautical engineer.

But Melitta’s private life almost led to her downfall. Her husband was Count Alexander von Stauffenberg whose army colonel brother Claus would later be executed for masterminding a failed plot to blow up Hitler at his military HQ in 1944.

The aftermath was lethal… Hitler was ruthless in his revenge on the Stauffenberg family. Her husband was imprisoned and Melitta was held for weeks for questioning by the Gestapo. She was only saved because of the importance of her war work and through the intervention of Nazi military leader Hermann Göring.

But Melitta had another potentially dangerous family secret… her grandfather was a Jew and although he did not practise his religion and Melitta was raised as a Protestant, Hitler’s race laws meant that she was classed as having ‘mixed blood.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAgain her brilliance as an engineer and test pilot, and her influential contacts, rescued her from almost certain deportation when her petition to be classified as of German blood and ‘equal to Aryan’ was accepted.

Both these remarkable women were driven by deeply held convictions about honour and patriotism but they could not have been more different and neither had a good word to say for the other. Their paths rarely crossed but they were mutually suspicious of each other and Hanna was frequently vicious and vocal in her criticism of Melitta.

Melitta died in April 1945 when her small plane was shot down by the Americans… she had been trying to track down her husband Alexander who was among a party of VIP prisoners being moved from one camp to another. Ironically, he survived the war and she didn’t.

Hanna died aged 67 from a heart attack in 1979, still consumed by jealousy of her rival and still in denial of Nazi wartime atrocities.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMulley’s gripping and revealing account of the contrasting yet strangely parallel lives of these two women, set against a changing backdrop of the 1936 Olympics, the Eastern Front, the Berlin Air Club, and Hitler’s bunker, reads more like fiction than a biography.

Packed with fascinating detail about their lives, their motivations and the forces that drove them to defy convention and risk their lives in the skies, this is an ambitious, well-researched and compelling story that opens up a new and fresh perspective on the role of women in the Second World War.

(Macmillan, hardback, £20)