Libraries come to town!

Last week we looked at early libraries which were not free to the public. A number of readers have pointed out that I have not mentioned them all, but one reader did chastise me for not referring to the Library that was associated with the Grammar School.

This Library, of course, still exists but it has been lost to Burnley and is housed at Lancaster University. It is a typical grammar school library of the 17th and 18th centuries, with a number of books from the 19th. The Burnley Grammar School Library is important in that it has survived but, these days, it is my opinion that it is only of interest to the academic.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs indicated, last week, Burnley was granted the status of a Borough in 1861 and, from that time, the demands for a public free library became increasingly audible. I have often wondered why the new Council took so many years to do anything about the demands for such facilities and I have come to the conclusion that, when first formed, the Council had so much to do that, to them, a free library service was way down their list of things to do.

In 1861 Burnley had very few municipal facilities. There was, for example, no town hall – the first members of the Council met in one of the rooms of the old Manchester Road fire station. There were no public parks. The town was not paved properly and there was no efficient sewage system. In addition there were no publicly owned places of entertainment and Burnley possessed no public sporting facilities.

The town had grown without the benefit of planning regulations and many of its buildings, some of which had been intended as living quarters for the rising manufacturing classes, quickly degenerated into slums. This can be seen in areas like Wapping which stood between St James’s Street and Cannon Street, now part of the present Charter Walk Shopping Centre.

Though there were many back-to-back and cellar dwellings in this area, a number of the properties has been well built, like the miller and brewers house at the corner of Cross Street and Bridge Street, later the site of Webster’s one of Burnley’s department stores. This building was once an impressive, double fronted residential house but it quickly was converted into a pub and then what we would call a house in multiple occupation, a lodging house, little better than a doss house.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn fact the quality of much of Burnley’s housing, even in 1861, was very poor. It was badly built, erected on the flood plains of both the Brun and the Calder and much of it was adjacent to mills, iron works, fell mongers and other undesirable industry.

It is possible that libraries, in these circumstances, were thought not to be a priority. In addition, though central government had been giving increasing grants to education since 1833, the provision of schools for poor, or working class, children was thought, even in the mid-19th century, to be the responsibility of the churches and the charities associated with them.

There were plenty of schools for those who could afford to pay fees and successful businessmen made sure that their sons, and daughters to some extent, attended them. They might have been first generation industrialists but they had no need for church schools. The story of education in Burnley is something else that I might look at in the future, but if this was the attitude to education at the time, and I think that it was, it is hardly surprising that public free libraries took some time to develop in Burnley.

By the 1880s the demands for a free municipal library were becoming more audible. In 1887 the Trades Council, an organisation which represented working men, passed a resolution that the Borough, now on the verge of becoming a County Borough with much greater powers, establish a Municipal Free Library. A year later the Trades Council asked for a room in the new town hall to be opened as a library but they were refused.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1891 the request for a free library was made again but nothing was delivered. From that year until 1898 a request was sent annually, from the Trades Council, that a free library be opened in Burnley but nothing was done.

Though local politicians had voiced opinions on whether there should be a free library, or not, it was not until 1897, when Mr Daniel Irving pledged the support of the local Socialists to the cause of a free library, that it looked as if anything might happen.

Mr Irving was to become Burnley’s first Labour MP but that was in 1918 and, even then, the town did not have a municipal free library. In his early political career Mr Irving had been an active member of the Social Democratic Federation, a very left wing political party funded, perhaps surprisingly by a London stockbroker, Mr H. M. Hyndman, who stood for Burnley in four general elections between 1895 and 1910.

Mr Hyndman was unsuccessful in all of these elections but the party which he largely funded, and other socialist groups, championed ideas like free public libraries. As you will know that, when the Labour Party was formed, the SDF became one of its constituent members pushing forward ideas which included free education for the poor and free public libraries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1898 it looked as if something might be done. A Joint Committee of the Council and the Trades Council was set up. It met annually but no funds were granted to it and virtually nothing was achieved. This situation might have continued for a long time but, in 1913, just before the First World War, a free library was opened in Trafalgar Street in Burnley.

It had, however, nothing to do with the Council and was the bequest to Burnley of Mr William Marshall, the late owner of Marshall’s furniture stores on St James’s Street in the town. Though a businessman, Mr Marshall was a principled socialist much affected by the writings of William Morris and, particularly, of John Ruskin. He had seen the advantages of having free public libraries that other towns enjoyed and he was determined that Burnley should not miss out.

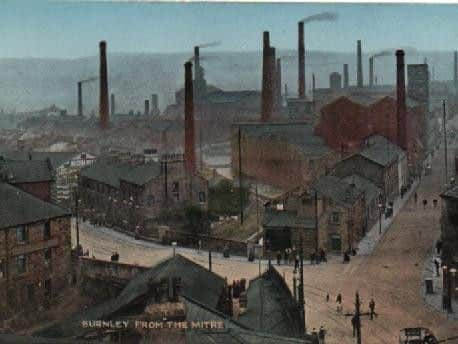

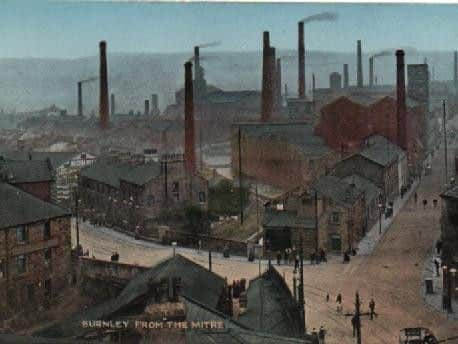

In fact Mr Marshall should be much better known than he is today. It was through him that Burnley got its first free public library which opened on February 28th, 1914, as a lending and reference library at the Mitre end of Trafalgar Street. Eventually, of course, and as we shall see, Burnley did get its Municipal Free Library but, for many years, the Marshall Library, and as part of the municipal offer, continued its work for the very populous Trafalgar Street area.

If you know Trafalgar Street today you will be aware that the Marshall Library no longer exists but it is not completely forgotten, or is it? I have not checked, in recent years, but there used to be a large stone in the wall indicating the site of the Marshall Library. That is my task for the week ahead – I am going to check if the stone is still there, and wo-be-tide the UTC if it is not!